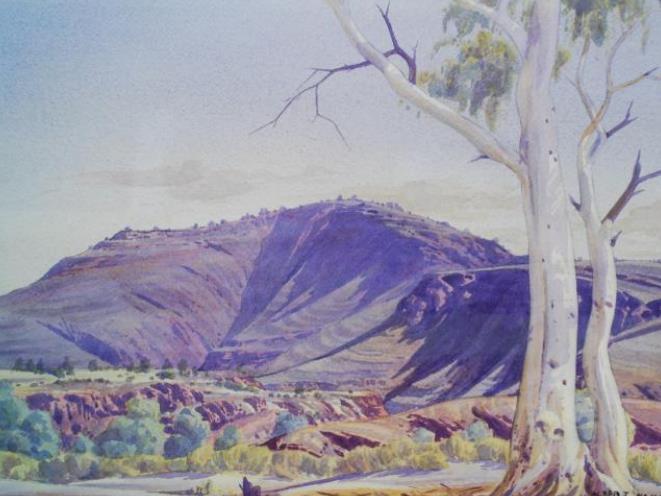

Albert Namatjira’s Mt Hermannsburg, c 1949-59. Araluen Art Collection, on loan from Ngurratjuta Pmara Ntjarra Aboriginal Corporation; Courtesy of Namatjira Legacy Trust.

The family of Australia’s first celebrated Aboriginal artist – Albert Namatjira – discovered with surprise that they had won a lingering copyright battle when they read it in the paper over the weekend.

Members of the family had been in Adelaide for the opening of Tarnanthi, the festival of Contempoary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art, where their project, What if this photograph is by Albert Namatjira? was being presented at the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA).

‘After a long battle we are happy to get the copyright back. For our future, for our children’s future and for our grandkids, and all our families,’ said Gloria Pannka, granddaughter of Albert Namatjira, in a formal statement.

The news had been broken by The Australian, which along with other media sources had applied pressure and raised awareness on the topic of Namatija’s copyright ownership. This battle started much earlier however, eight years ago when the arts lobbying organisation, Big hART joined with the Namatjira Family, The Namatjira Legacy Trust and pro-bono work by law firm Arnold Bloch Leibler to fight for the return of the copyright to Albert Namatjira’s works to his descendants.

Scott Rankin, CEO, Big hART told ArtsHub: ‘It is like body surfing. There’s nothing out there and then a wave comes and suddenly you’re on it. We knew it was in the offering, but it happened really quickly. It was touch and go there for a while and then Friday (13 October) lunchtime the Deed was signed.’

The catalyst for that signing was the involvement of entrepreneur and philanthropist Dick Smith and a $1 deal.

Smith’s father, Herb, had worked for Legend Press founder John Brackenreg, the Sydney art dealer who represented Namatjira. Legend Press acquired the copyright to Namatjira’s works from the NT government in 1983 for just $8,500.

Using that connection, Smith reached out to Brackenreg’s son, one of the current owners of Legend Press. It is said that the deal was done within 15 minutes over the phone.

Rankin explained: ‘A few weeks out from the signing we heard that Dick Smith had this personal story, and he came to us and said “Let me give them a call.” He offered to put up the money for the Copyright sale, but they said no to a lot of money and were happy with just a $1 exchange.’

Smith then donated $250,000 to the Namatjira Legacy Trust – which was established in March this year – in recognition of John Brackenreg.

‘It wasn’t as if there was any great, difficult battle; the phone call took about 15 minutes, and Philip was very much in agreement with solving this problem,’ Smith told The Australian.

In a nutshell: The Deal

- In 1957 Namatjira entered into a legal agreement with publishing company Legend Press. This agreement stated that Legend Press would pay royalties to Namatjira in exchange for having the sole right to reproduce all of his paintings. In return for this licence, Namatjira received an ongoing economic benefit through royalties or licence fees. However he still owned his copyright.

- In 1959 Namatijira died. His will left his estate including his copyright to his family. The Public Trustee for the Northern Territory Government was responsible for administering the will and his estate. When the agreement concluded in 1983, the Public Trustee decided to sell the copyright to all his works for $8,500 to John Brackenberg of Legend Press, without consulting the family. The Trustee, John Flynn, recently told the ABC that this decision was a mistake, which he now regrets. Rather than the subsequent fifty years, he believed they were signing a deal for seven years, rather than the full 27.

- Big hART was invited into the Hermmansburg community by the Namatjira family over 8 years ago to help bring about change and renewal.

- Big hART produced the theatre production Namatjira, which toured nationally and internationally from 2010 – 2013 and reached an audience of over 50,000.

- Between 2010 and 2017, Big hART staged 23 contemporary watercolour exhibitions and created a CD and an App, all focused on broadening awareness of the Namatjira copyright campaign.

- Big hART facilitated a private meeting with the Queen at Buckingham Palace for the Namatjira family, as a catalyst for media attention on the copyright issue.

- March 2017: the independent foundation ‘Namatjira Legacy Trust’ was established to preserve and protect the Namatjira family legacy and support the sustainability of the Hermannsburg Watercolour Movement.

- 2017 August-October: the feature documentary, Namatjira Project premiered at Melbourne International Film Festival, went on to screen at the Brisbane Film Festival, Adelaide Film Festival, Cinefest Perth, Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair and in cinemas around the country.

- October 2017: exhibitions of Albert Namatjira and the Hermannsburg artists are presented at the National Gallery of Australia, the Queensland Art Gallery and the Art Galley of South Australia, adding to the momentum.

- 13 October 2017, pursuant to the Deed, Legend Press Pty Ltd assigned copyright to the Namatjira Legacy Trust for a nominal fee of $1, negotiated by entrepreneur Dick Smith AC.

- Dick Smith donated $250,000 to the Namatjira Legacy Trust in the name of John Brackenreg, founder of Legend Press.

- Namatjira’s family have earnt no money from copyright or royalties from reproductions of Albert Namatjira’s works since 1983.

- From 2010, the family has been entitled to 5% of the resale cost of any Namatjira works, which will continue until 2029 when the copyright expires.

The long-term implications of copyright sale

An Arrernte man from Central Australia, Namatjira is recognised as Australia’s greatest Indigenous painter and the first to work in the western tradition. He is best known for his watercolour paintings of the outback, and created about 2000 artworks during his life. He was an innovator, also taking to the camera, thought of himself as a teacher, and influenced a school of painters, now known as the Hermannsburg Watercolour Movement.

Despite that influence, the use of images of Namatjira’s works have been tightly restricted, with some claiming that it had stifled his legacy. A good example was the Art and Soul television series by Hetti Perkins and the Battarbee and Namatjira book by Martin Edmond which both did not contain images from Albert Namatjira’s artworks. That invisibility has enormous implications for all of Australia.

‘It may seem like a simple legal shift but it is a momentous occasions. Albert’s work has been returned to family, to country – history has changed this weekend,’ said Lisa Slade Assistant Director Art Gallery of South Australia.

Installation view and panel discussion with Namatjira family members and Lisa Slade at Tarnanthi, Art Gallery of South Australia the morning after the announcement.

Last week’s agreement means royalty payments will again flow to the Namatjiras and their community, via the Trust.

What it also means is that through the family’s control, Namatjira’s work can be reproduced in everything from gallery catalogues and websites to merchandising, films and school textbooks.

‘We really want his images to be more available so the family can see them and the younger generation can see them,’ said Pannka.

Copyright expires in 2029. The Legacy Trust will apply for an extension to that copyright given the suffering the family have undergone. Slade said: ‘There is international precedence with this, and it has happened with Peter Pan.’

Will the family continue to fight for compensation?

Pannka, on behalf of the family, and Sophia Marinos of Big hART, confirmed that a legal campaign to tackle Northern Territory authorities over their historical involvement in this injustice would continue.

Rankin told ArtsHub: ‘It has had a very real cost to the family’.

It is estimated the Namatjira descendants suffered heavy financial losses because of the six-decade copyright dispute.

‘It is always very important that you don’t build a dependency model; to leave when the job is done. The Namatjira Trust becomes the profile now. There is a compensation argument to be made for the family. That will go on as the next part of the campaign, but it is the Trust’s campaign now,’ said Rankin.

He noted that projects like the Namatjira campaign always empty the coffers, and that as a campaigning organisation is hard to operate without funding support.

‘This is our 25th year of the company. We started at the same time as Bell Shakespeare and Bangarra Dance Company, and yet we have received nothing from the Australia Council – we only been invited to apply for project based funding. There is a real policy deficit there that disadvantages companies like ours.’

Rankin was keen to add that the Namatjira campaign also pointed to another story, largely overlooked.

‘Albert Namatjira started the Aboriginal Art Centre movement in Australia, and now there are over 100 art centres. They are incredibly important to the wellbeing and cultural health of those communities, and as a society we don’t back these remote art centres, and they are struggling. We are happy to take contemporary Aboriginal art to the market and flog the hell out of it – but there is a real need for policy to support these centres financially,’ he said.

Momentum rather than adversarial action

Rankin believes that campaigns are not won by taking the sledge-hammer approach. You have to build the narrative into the public’s heart. ‘A lot of the campaigning world takes an adversarial role, and as soon as you do that, you become part of the problem.’

He continued: ‘At Big hART we look at the story. Brackenreg is part of that story and there are aspects to it that were very good and respectful at its time. But then it went wrong in 1983 due to policy negligence.’

Big hART’s mission reads: ‘Our work sheds light on invisible stories, bringing hidden injustice into the mainstream.’

Rankin said: ‘We are pretty strategic these days and have learnt how to build the momentum. You can’t go and just get word out there and go online. It is the end game that you have to keep in sight, and that requires that people get a sense of the issue and an authentic experience of that narrative. We can effect change in this way.’