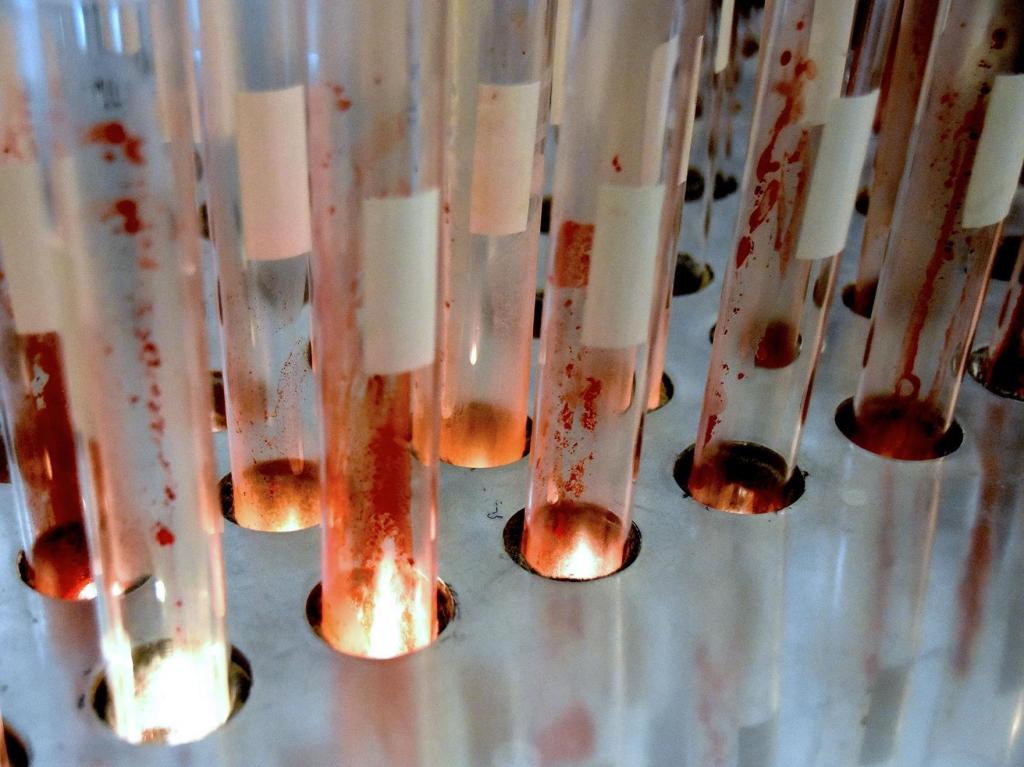

Fiona Davies, installation view, Blood on Silk Buy Sell, in Science Gallery Melbourne exhibition; supplied courtesy the artist

An unusual trend has recently taken over our galleries and museums: a renewed fascination for blood as a creative medium.

I say ‘renewed’ as working with blood is not a new idea. As a medium it gained traction in the 1960s with the rise of performance art and feminism, and has been used by artists as a symbol of protest, a symbol of gender, of birth right and, more recently, as a bridge for well-funded arts-science collaborations.

So what is the platform chosen in this current swell of exhibitions, and why are so many artists turning to blood today? The Science Gallery Melbourne (SGM) reports that over 350 proposals were submitted in response to their global call-out for ideas for their exhibition, BLOOD: ATTRACT & REPEL. That’s a lot of bloody interest!

Mike Parr performance at National Gallery of Australia, August 2016; Photo ArtsHub

Over the past year we have seen Mike Parr extract his own blood in a performance (pictured above) and then paint with it in an ode to Jackson Pollack’s painting Blue Poles; we saw protests against Austrian artist Hermann Nitsch in Hobart, when it was announced that he would slaughter a animal and use its blood for a Dark Mofo performance, and we were witness to the world’s outrage over President Donald Trump’s comment to journalist Megyn Kelly – ‘you could see there was blood coming out of her eyes. Blood coming out of her wherever’. In response, American artist Sarah Levy created a protest portrait of Trump from her own menstrual blood.

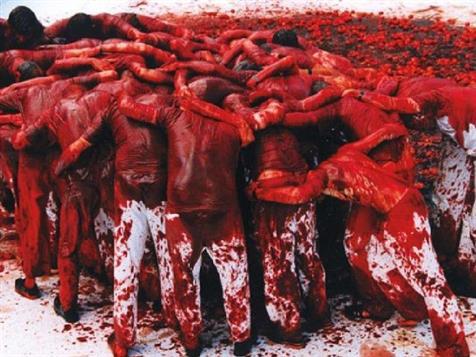

Publicity image for Nitsch’s work; supplied

It’s been a long letting

Nitsch has been using blood, urine and faeces in a ritualistic way since the early 1960s. Actually, Nitsch has been to prison three times over his blood-drenched, ritualistic art work, so a protest by animal rights activists could hardly come as a surprise.

Similarly, blood was often used by artists in the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s both as a subject and a material of protest. As art historian Kate MacNeill recently wrote of that time, ‘Blood was dangerously out of place.’

Tracey Emin’s blood-soaked tampon appeared in her Turner Prize nominated work My Bed, and Judy Chicago’s iconic feminist art installation, Menstruation Bathroom as part of Womenshouse (Los Angeles, 1972) are among the more well known works in this field.

In response to the HIV-AIDS epidemic in western gay communities, artists explored a world where where, ‘suddenly the metaphors of blood, pure and impure, clean and unclean, became frightening literal.’ Andres Serrano photographed images of blood and other body fluids in his Blood and Semen series (1990). Franko B’s performance work I Miss You, in the Tate’s Turbine Hall (London, 2003) saw him naked, with blood flowing from cuts to his arms and seeping into a canvas covered runway.

Then we turn to, perhaps, the most famous use of human blood by an artist, the busts created by British artist Marc Quinn. Every five years, he creates a Self (1991-1996), a cast of his head from 4.5 litres of his own blood, drained from his body over a period of five months and frozen in a mould. The resulting bloody frost comes with its own refrigeration unit.

Most of the heads are in private collections, and in 2009, one of them was sold to the National Portrait Gallery in the UK for $465,000.

Marc Quinn likes to see himself in blood

All these artworks are benchmarks to past social mores – pushing us to new thinking, new acceptance. While it is easy to get caught in the past, as blood is such a fabulous social laboratory in the hands of artists, we are more interested in what these current exhibitions say about Australian audiences today.

Blood as Science

Described as part exhibition and part experiment, the inaugural exhibition of the Science Gallery Melbourne takes a look at blood from the scientific to the symbolic. In other words, the whole gamut.

Less political and more populist, it appeals to the human sense of fascination and a kind of geeky hands-on immersion. Really it says more about museum trends than our current social condition.

Science Gallery Melbourne’s Creative Director and curator of BLOOD: ATTRACT & REPEL, Dr Ryan Jefferies (who has a PhD in infectious diseases and did home taxidermy as a kid) said: ‘From kinetic sculptures that explore synthetic blood to levitating blood cells, the exhibition will be multi-layered and a challenge to the senses.’

Among the works on show are a bloodletting cupping set c 1830, and The Mums, a series of large-scale photographs of squashed mosquitoes that fed on South Korean artist Jipil Jung’s own blood to nourish their developing eggs. Penny Byrne’s installation Blood Diamond (2017) is inspired by cutting edge research at Monash University into malaria.

Nearly half of the world’s population is at risk of malaria. But, despite around 212 million cases reported in 2015, deaths from the disease are have dropped dramatically since 2010. On entering the room that contains Byrne’s work, visitors face a large single red blood cell that seemingly levitates and glows. Technology augments the space and reveals the hidden parasites.

.jpg)

Installation view, Penny Byrne’s Blood Diamond; courtesy the artist and SGM, supplied

Among the more quirky projects is the collaboration between Marion Laval-Jeantet and Benoît Mangin, May the Horse Live in Me!, presenting a blending of human and animal blood.

MacNeill says of their work: ‘Over time, Laval-Jeantet built up an immunity to horse blood, sufficient to enable her to be injected with horse blood plasma as part of an experiment that they describe as a “foray into human/animal ‘blood-sisterhood’”.

‘This work can also be seen as a response to the hubris of the anthropocene, the implicit assumption that humans are something other than animal. Ultimately this seems to be the common thread in these artworks: each asks questions of the ways in which humans are gendered, categorised and deemed separate from animals and from each other.’

Marion Laval-Jeantet and Benoît Mangin, May the Horse Live in Me! at SGM

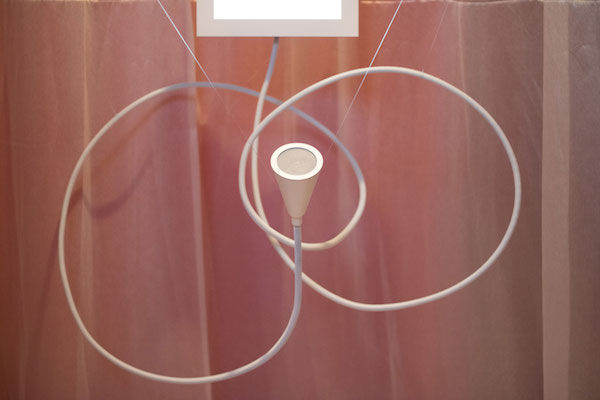

Taking a different tone is the new work, Sentience (2017) by artists Ollie Cotsaftis and Sarah McArthur (AU), which explores our innate response to the smell of blood. Are we unconsciously led by our biases, instincts or genetics?

The smell of blood is produced by a single molecule trans-4,5- epoxy-2(E)-Decenal, a powerful olfactory signal that innately triggers a physiological response. It is believed that much of our emotional response to smell is governed by association, explaining why individuals perceive the same smell differently.

Installation view, Sentience, courtesy the artists and SGM; Photo Jessica Vovers

Also on show is an installation by The Hotham Street Ladies (a collective based in Australia, UK and Berlin) that has been described as ‘a homage to Chicago’s Menstruation Bathroom.’

A toilet cube mural created in confectionery icing, it uses no blood but offers a saccharine take on the birds and bees/feminist lesson.

Also echoing the past, Irish artist John O’Shea attempted to draw blood from a living pig to create his Black Market Pudding, but apparently, no Australian farmer was willing to provide a pig to be bled.

MacNeill said: ‘The work has been produced elsewhere – highlighting how our industrial, legal and ethical frameworks make it easier to slaughter an animal than bleed one, but keep it alive.’

It might be the political high point, and local touchstone, of this exhibition – one that will likely be overlooked among the more spectacular works.

Science Gallery Melbourne is embedded within The University of Melbourne, with new purpose built premises in Grattan St scheduled to open 2020. In the meantime, BLOOD: ATTRACT & REPEL will be held at the historic Frank Tate building at The University of Melbourne and satellite venues across the city from 2 August – 5 October 2017.

Blood as Life Commodity

Blue Mountains-based artist Fiona Davies has been obsessed with blood since she met the late physicist Dr Peter Domachuk from the University of Sydney. Their collaborative project with writer Dr Lee-Ann Hall, Blood on Silk, scans from the material, culture and economics of silk and blood through to issues of surveillance and associated concerns about human rights.

Davies said: ‘During the years following the death of my father in 2001 I have worked with ideas of medicalised death and particularly the almost domesticated rituals in an intensive care ward involved in taking daily samples of blood.’

I’m really interested in contemporary medical practices and how they interact with ethics, with economics, with that sort of emotional landscape,’ she told Scoop.

As the inaugural recipient of the Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre Turbine Hall Commission – in western Sydney – Davies has draped 800 square metres of handmade silk paper across the 30m-deep expanse of the hall, dividing the space into five makeshift hospital rooms.

Entitled Blood on Silk: Last Seen it is an examination of medical dying in Intensive Care Units, accompanied by video that replicates the endless bustle and emotional landscape of hospital environments.

It is interesting timing given that the Victorian state government is planning to introduce laws allowing patients to initiate a request for assisted dying. According to today’s The Australian, ‘The Victorian government is set to introduce assisted-suicide legislation into state parliament within a month, with the aim to legalise the reform by the end of the year.’

Installation view, Fiona Davies’ blood inspired work at Casula Powerhouse.

Davies’ installations are usually intimate and object-based, have a faux-medical quality, and are often washed with projections that activates their narrative. Her work in the SGM exhibition, Buy Sell (pictured top) focuses on the materiality of blood. The work considers the daily ritual within ICU of sampling blood for external testing.

They present a kind of “slow bleed” of ideas to audiences – which, while ethereal and beautiful in presentation, are often sitting at the pointy end of the big topics. Blood on Silk: Last Seen is showing 21 July – 17 September.

Casula is hosting The Space of the Biomedical Body Symposium on 23 August (11am – 1pm), bringing together artists, curators, researchers and scientists to artists, curators, researchers and scientists. More detail.

Blood as Memory

While less about blood, and more about violence and blood lines, Greg Semu’s exhibition BLOOD RED brings together a body of new, large-scale photographic works completed in Coen, a remote Indigenous community in Cape York, Far North Queensland.

They render archival and remembered testimony of their experience as a chorus of silent injustice that challenges colonisers’ accounts of Australian history. Semu uses blood to make a very powerful point.

Head shot with chain and friends from the BLOOD RED series, 2016/2017, pigment print on art paper, 120 x180 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Alcaston Gallery, Melbourne.

Writer Andrea Simpson says: ‘Semu has worked like a filmmaker, zeroing in on, re-enacting and upscaling as gigantic photographs the brutal evidence of Coen’s frontier wars for the purpose of remembering the past and acknowledging present injustice and discrimination.’

Inside the blackened gallery space will be a room studded with recessed keyholes that will allow visitors to peer discretely at the original photographs of events.

Working in consultation with Coen artist Naomi Hobson and community elders, the exhibition is at once confronting and game-changing – enslaved Aboriginal prisoners are unchained, the roles of the black and white protagonists are reversed… and blood is let.

Blood in the hands of Semu is a powerful reminder of the past, of violence and racial inequalities and the right of bloodlines. BLOOD RED is showing at the Cairns Art Gallery from 12 July – 17 September.

Read: Sami Blood review