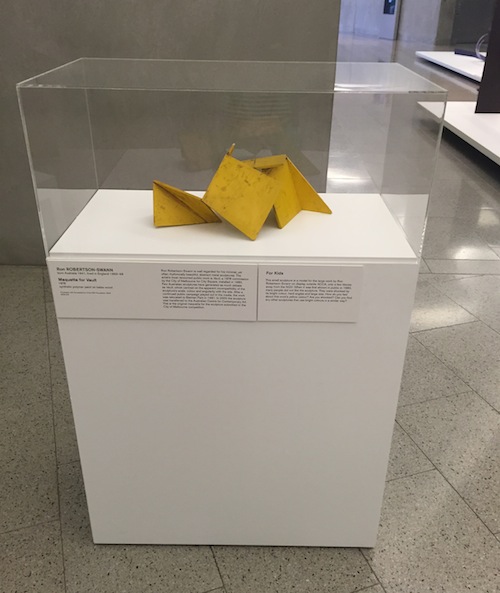

Clive Murray-White’s Untitled yellow sculpture (1970); Collection NGV

I felt really torn about this exhibition.

While I tip my hat to the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV Australia) for giving sculpture warranted weight in its exhibition program, I felt critical that they didn’t go that step further and site the exhibition in one of the galleries, but rather relegated it to incidental foyer art.

I know there is logic in that decision. Simply sculpture is cumbersome and foyers are generally vast empty caverns – why not activate them? It would appear to be a natural win-win. But unfortunately reality paints a different picture.

While exposure may be heightened by using the more public spaces, any thoroughfare is not an inducive environment for considered contemplation and, as a result, the work is done a disservice from that the very transitory nature of the space.

The bottom line is that we are conditioned to move through foyers enroute to somewhere else.

Installation view Hard Edge at NGV Australia. The architecture and transition zone fight with the artworks making them feel incidental; Photo ArtsHub

As a curated exhibition – opposed to the stand-alone pop-up sculpture that the gallery has done very successfully in the past – there is a kind of trade-off at play: get it out of storage but settle for the compromise of “glance art” status.

The title of this exhibition, however, gives it the weight it deserves: Hard Edge: Abstract Sculpture 1960s-70s. It caught my eye and dragged me in for a review. But upon entering the gallery and moving through the exhibition I was plagued with confusion – what was included and what wasn’t? Had I seen it all?

A neon sculpture by Jonathan Jones presented on an upper level, Blue Poles (2010), is case in point. While it was not part of this exhibition, it was also placed in the foyer areas of the galleries and could be easily mistaken by the unknowing as part of that abstract conversation of the period, as explored by international artists such as Dan Flavin, Robert Irwin and Ivan Navarro.

Confusing matters as Jonathan Jones‘ Blue Poles was also placed in the gallery foyers; Photo ArtsHub

I was also derailed by exhibitions in the adjacent galleries mid-viewing, which amplified the kind of staccato engagement that an exhibition presented this way across foyers and landings creates.

They are harsh criticism for a laudable and well-curated exhibition.

If the group of works was presented in a singular gallery space I think my reception of the exhibition would have been very different – and dare I add, encouraged to engage with in a more serious tone.

It raises the question, then, how much of the viewing experience determines our opinion of the art we view, and are such criticism valid when reviewing an exhibition?

In a recent interview with the curator of this exhibition David Hurlston, he said: ‘The difficulty has been that a lot of institutions do not have the space to show sculpture per se.

‘One of issues with sculpture – curatorially – is that it is often large scale and the ability to be able to exhibit it well is often difficult,’ he continued.

I have to agree with Hurlston’s motives, then, to turn to the foyers and get these pieces out of storage.

So, if we can push all that aside and blinker our opinions from the viewing experience, then we are faced with a stunning and erudite line-up of sculptures assembled by Hurlston.

Hard Edge: Abstract Sculpture 1960s-70s dips into the decades in which sculpture found its mojo in Australia – a period when ‘sculptors experimented with new trends and embraced an adventurous style of abstraction, tending towards the minimal style seen in New York City’, the gallery explained.

While this springboard for change was a glance towards the International spectre (and we tended to have a myopic glance during that time), what this exhibition articulates is our own voice found parallel to those global trends.

‘Hard Edge captures a defining moment for Australian sculpture when artists began to shift away from traditional carved stone, wood or bronze and move towards modern materials and techniques, reflecting the advancements in technology throughout the 1960s and 1970s. This new style was characterised by often highly polished and brightly coloured abstract forms,’ explained Tony Ellwood, Director NGV.

Abstraction had clearly emerged.

The 13 sculptures Hurlston has chosen to narrate that story include works by Clement Meadmore, Inge King, Jock Clutterbuck, Clive Murray-White, Lenton Parr, Ron Robertson-Swann, C. Elwynn Dennis and David Wilson.

Among the earliest artists to produce work following this Hard Edge line were Lenton Parr (who had worked as an assistant to British sculptor Henry Moore in the 1950s) and German-born Inge King, who arrived in Australia in 1951 with a modernist zeal and passion to raise the profile of public art.

The exhibition pulls out pivotal early works by both artists.

But the exhibition also tracks the rise of contemporary sculpture in Australia, fueled by major events such as The Mildura Sculpture Triennial – the first comprehensive Australian event dedicated to large-scale sculpture established in 1961 – the NGV’s Recent Australian Sculpture exhibition which toured nationally in 1964, and the iconic NGV exhibition The Field of 1968 which was deeply influential on both painting and sculpture – as well as audiences.

Tony Coleing was included in The Field with three large sculptures, and one, Frondescence (1968) appears in this exhibition.

So you start to see the weight and significance this exhibition holds.

The biggest noise however came from the smallest sculpture in this show, Robertson-Swann’s infamous sculpture Vault (1980), more commonly tagged the “yellow peril”.

Vault marquette, part of documentary recreation of Australia’s “most hated sculpture”, and its importance to sculpture’s history.

This exhibition marks 35 years since its initial installation in Melbourne’s City Square, before being moved to Batman Park just six month later in a covert overnight operation, where it languished for the next two decades.

It polarized public opinion and was a political pawn.

Hurlston said: ‘It would barely raise any dust at all today. In hindsight it certainly raised his reputation and put sculpture in the public spotlight.’

‘Sculpture is today very different, and it has benefited from that ground breaking role that those artists of the 1960s played,’ he added.

It is this foundation that percolates beyond the heavy metal weight of most of these pieces and turns to sculpture as a read of Australian society. It offers an interesting back story or frog leap to where we sit now.

But there is a stumble here.

While the gesture was to reinstate the importance of this work, sadly its placement does not match that intent.

The documentation of this pivotal work – its marquette, a video and ephemera – are pushed into a corner and to the side of an entrance to a main gallery. It comes across as side-lined.

We are a public that has become comfortable with the outdoor sculpture festival and have learnt to enjoy living with public art, so the idea of an exhibition that links that back to our collecting institutions and looks at some of sculpture’s origins in Australia – as well as tracking a good juicy scandal – surely, I would have thought, ticked the accountability box for a public institution.

What this exhibition has done, for this viewer, is trigger a deeper discussion about how we value sculpture today, and I suppose in that there is success in its motives.

Hurlston mentioned that an exhibition of Bruce Armstrong’s sculptures will follow Hard Edge later this year and Akio Makigawa next year in the foyer areas. This is a considered commitment.

However, I think Vault remains a metaphor for moving forward.

It is now described “at home” in a location that celebrates its aesthetic and history – it has been sited at Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) in Melbourne’s Southbank since 2002. But to a critical eye, the sculpture sits not at the entrance in bravado and a place of pride, but faces an intersection and is backed by amenities at the building’s rear.

Simply compromises – however well intentioned – do not work well.

I salute NGV to continue its roll out of the sculpture collection and to curate shows that tackle a well-over due dialogue surrounding Australian sculpture, but encourage the institution to consider giving these exhibitions weight beyond the mere glance that a transitory zone dictates.

Leave them for the pop-up sculpture that leads the viewer in for more – not the full blown conclusion that feels slightly deflated.

Rating: 3 out of 5

Hard Edge: Abstract Sculpture 1960s-70s

The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia

13 February – July 2016

Free entry

Online essay