Installation view of Not Niwe, Not Nieuw, Not Neu with Daniel Boyd and Michael Parekowhai’s work; 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney; photo ArtsHub

Walking through this exhibition with curator Michael Do a week ago, he quipped: ‘Who’d have thought I’d be seeing Joseph Banks in an exhibition with these artists?’

Indeed, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (4A) presents a curious line-up with its current exhibition: Not Niwe, Not Nieuw, Not Neu. Colonial botanist Sir Joseph Banks sits alongside artists who are known for their interrogation of colonial histories: Daniel Boyd, Newell Harry, Fiona Pardington, Michael Parekowhai and James Tylor.

Not Niwe, Not Nieuw, Not Neu takes as its launch pad the 1768-1771 voyage of HMS Endeavour, led by the then little-known Lieutenant James Cook and accompanied by Banks, who collected over 30,00 specimens from Australia and New Zealand.

Do told ArtsHub: ‘For us it is a deeper understanding of the nuances of that trip. We tend to think of these colonial figures as terrible figures in post colonial theory, but more than just that easy labeling of them, we want to talk about them in a more articulate way.

‘We just gloss over things like the banksia, Cooktown, and Botany Bay. The perspective we wanted to come from was that this colonial prejudice is so interwoven into language and maybe insidiously so, and we are so comfortable with that; it is a gentle reminder of those origins.’

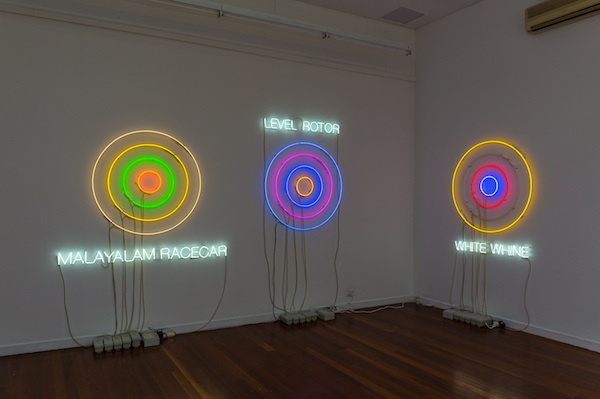

This is immediately apparent walking into the street-level gallery and viewing three neon works from Newell Harry’s series, Circles in the Round. Do described these entangled word-plays: ‘They mean nothing, but at the same time they mean everything – just this act of standing there trying to untangle it all. “What does this mean?” for him was a really powerful statement of what language can do for people. He has travelled so much and seen the effect of language on people – how it includes and excludes.’

From left to right: Newell Harry, Circle/s in the Round: MALAYALAM RACECAR, 2010; Circle/s in the Round: LEVEL ROTOR, 2010 and Circle/s in the Round: WHITE WHINE, 2010; neon, Courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney. Installation view 4A 2017

While the series is all colourful bling and punch, observed from the street and using the vernacular of the marketing, Do agreed there was a kind of disjuncture with the upstairs gallery, which is incredibly refined, elegant and minimal in its hang.

The threads of connection however, remain finely tuned across this exhibition. The anchor to the upstairs hang – and in fact the exhibition’s very premise – are two hand-coloured copperplate etchings that were printed by Banks, that have been modelled off the illustrations Sidney Parkinson created on the Endeavour journey. He never made it back to London, but his legacy did.

Banks never published them – they were only completed in 1980 – and sitting here in a contemporary art space that focuses on our region, they form a fresh and erudite springboard that is subtly provocative and questioning.

They are superbly paired with a suite of works by James Tylor that, with their mirror-like surface, turn to the colonial language of the daguerreotypes. In them you are drawn into this historical narrative.

They re-imagine Banks’ work as softly spoken metaphors, where the plants being taken away as specimens reference the ways we treated our First Nations people.

Detail of James Tylor’s becquerel daguerreotype from 2015 in 4A’s Not Niwe, Not Nieuw, Not Neu; Courtesy the artist and Vivien Anderson Gallery, Melbourne, photo ArtsHub.

Also in this space are two large-scale photographs by Fiona Pardington, which turn to the language of the museum specimen and still life to draw attention to the native flora, Puriri (which Banks collected on this journey) and the extinct, sacred Huia bird.

This notion of the introduced species and the vying tension between the coloniser and the colonised is played out beautifully in two works by Michael Parekowhai. Central to the exhibition sits a trio of lemon trees on a shipping palette, all cast in bronze. It is a stunning piece; it is also an intelligent piece.

According to Do, the lemon tree as we know it is native to nowhere, created through hybridisation. Lemon trees are also colonisers, brought on sea journeys to tackle scurvy and in order to grow something familiar on arrival.

Similarly, in the Beverly Hills Gun Club series, Parekowhai entertains the idea of “otherness” by taking the common sparrow and tracing its introduction to New Zealand by British colonialists, with the intention of making the ecology feel more ‘familiar’. But this coloniser became a pest to native species.

Left to right: Michael Parekowhai, Alex Hamilton (from the series ‘Beverly Hills Gun Club’), 2004; Dave Douglas (from the series ‘Beverly Hills Gun Club’), 2004, and J.D. Jones (from the series ‘Beverly Hills Gun Club’), 2004; sparrows with two pot paint, aluminium, Courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney. Installation view 4A 2017

Do explained the series title: ‘Furthering this is the fact that each of the birds is named after people and situations related to American handguns, alluding to the danger of these invasive colonial “weapons”’.

Each bird sits upon a refined green steel branch – a symbol of New Zealand flora and as Do says, a ‘beautiful ode to modernism’.

A review of this exhibition is not complete without a mention of two early paintings by Daniel Boyd, dating back to 2005 when he was painting in a different style. Here Banks is recast as a pirate and King George III – the monarch who commissioned the Cook journey and was a huge fan of Bank’s work – is labeled “King no beard”.

Do asks, through the works in this exhibition, ‘Who has the privilege of classifying something new, why, and to whom?’

Left to right: Daniel Boyd, King No Beard, 2008, Collection, Clinton Ng, and Sir No Beard, 2009, Courtesy the artist, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney and STATION, Melbourne. Installation view 4A 2017

This – Do’s first exhibition with 4A – is a very elegant show and one that has a very different scale and feel than others presented in the space. The conversation across the works is strong and, yet individually, each tells a very layered narrative. Do gently plays the role of provocateur – along with the artists he has selected.

It is hard to find fault with this exhibition. It is the kind of show that opens to fresh thinking and conversations without sledgehammer repercussions.

As Do concludes: ‘The British colonial project, whilst yielding incredible botanical discovery, left a legacy of social, economic, political and literary devastation of Aboriginal communities that continues today.

‘Whilst not directly addressed in this exhibition these considerations are present and inform these artists’ practices, galvanising their stories and observations. This is the strength of these artists. Through provocation and questions, they provide us the tools to forge a new order from the precarious vestiges and remainders of the so-called colonial “new world”’.

Rating 4 ½ stars out of 5

Not Niwe, Not Nieuw, Not Neu

Artists: Sir Joseph Banks, Daniel Boyd, Newell Harry, Fiona Pardington, Michael Parekowhai and James Tylor

27 October – 10 December

4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art

Hay St, Sydney

Free