Installation view Vernon Ah Kee’s exhibition Not an animal or a plant at NAS Gallery, Darlinghurst; photo Artshub

Vernon Ah Kee’s work has been shown at the 2009 Venice Biennale, the 14th Istanbul Biennial (2015), in Sakahàn, the 1st International Quinquennial of New Indigenous Art at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (2013), and, yet, this is the first major solo survey of his work on home soil.

In his eyes, he feels that there has been an unwillingness to take on the tough subjects in Australia. He didn’t mince his words when our conversation turned to Australian conservatism.

‘When you talk about Aboriginal content it is usually the softest Aboriginal content that people can achieve, unfortunately.

‘In regards to Aboriginal content and ticking boxes, it is consistently the softest and you get political artists whose politics are only ever achievable.’

Does Vernon follow suit with his own solo exhibition? The gallery states: ‘His determined voice is driven by an unwavering commitment to address the situation and experience of Aboriginal Australians.’

The National Art School (NAS) exhibition, like many museums and galleries I would argue have listened by showing and collecting the work of many Contemporary Aboriginal artists, such as Tony Albert, Destiny Deacon, Richard Bell, Fiona Foley, Jason Wing – all of whom Ah Kee has exhibited in their company and who have been very hard-hitting in their identity politics.

Today, their works are the benchmarks for Contemporary Aboriginal art. One might even ponder can urban Aboriginal art be contemporary unless it is “political”?

Rather, I think that the trigger conversation here is that we have become so wrapped in cotton wool sensitivities and confusion that the art world has censored itself from a critical lens when it comes to discussing Aboriginal art. I admit that I didn’t write about Indigenous art for years as I felt it “wasn’t my place.”

Whose place – and the kind of abstract permissions and perceptions we impose – sits core to Ah Kee’s exhibition at NAS Gallery, titled Not an Animal or a Plant.

It is a reference to the 50th anniversary of the 1967 referendum in Australia, which recognised Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as people and included them in the census.

When Ah Kee was born he was denied that human right. It is perhaps one of the reasons his portraits take on an even stronger presence and monumentality in this exhibition.

Ah Kee said flatly on the topic: ‘I am not an error of history; this is my life.’

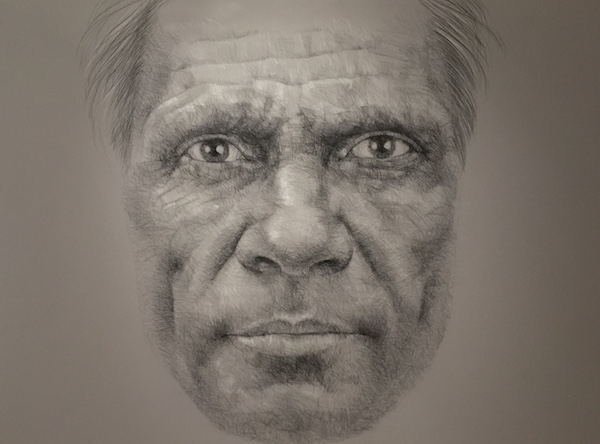

We are familiar with Ah Kee over-sized charcoal and pencil drawings that are largely of his family members and ancestor, almost as a way to validate them. They don’t immediately strike us as political. They are also unmistakably about humanity – it is a personal story.

Plus, Australians are gooey for a good portrait, and Ah Kee delivers.The lower gallery space is dominated by his drawings in a well paced and empathetic delivery.

George Sibley (2008); Collection Catherine Elms and Richard Williamson, Brisbane, courtesy the artist

But that intent of personal narrative seems to shift and dodge, to emerge and retract over the last twelve years that this exhibition surveys.

Towards the rear of the lower level gallery, tucked discreetly in a corner, is a suite of found objects with the title Born in This Skin (2008) – toilet doors removed from Cockatoo Island and re-purposed. They are covered with hateful racial and gender slurs, and were presented in-situ as part of the 2008 Biennale of Sydney.

The implication is that in their installation they are “authored” by Ah Kee, and in their re-presentation he is over-riding them with a new message – let’s call it a “reverse finger point”.

Critic Andrew Frost ponders whether its intent is divert attention towards the racism of the art world itself.

Installation view Born in this skin (2008); Courtesy Sydney Harbour Federation Trust

That agitation continues upstairs with a group of large new works. Gracing the end wall with a kind of religiosity is a pair of drawings of faceless figures with scarified bodies and their hands bound.

Ah Kee explained of Lynching I and II (2016) were images of dead bodies. ‘Their voice is universal. They could be anyone. They are about the cruelty and brutality of lynching.’

In them the scarification of initiation is blurred with the burnt and scared flesh of lynching. Ah Kee made them in situ at the College of Art in Brisbane, the charcoal flaking from the rough canvas to the floor. He explained: ‘For me they were residue of process, but also referred directly to the process of lynching and burning a body where you have the residue of the body.’

Installation view of Lynching II and Lynching I (2015); Courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane

Floating in front of them is a suite of new custom surfboards, Authors of Devastation (2016), which appropriates rainforest shield designs and on the verso grabbed sound-bites from the US civil rights movement.

It is not the first time that Ah Kee has used surfboards in this way, making particular note that the new form was a competition board, playing off white-black race tensions and the kind of frictions and disjuncture as cultures class from traditional tribal to neo tribal.

Authors of Devastation (2016), installation view NAS with painting Many Lies in the background; photo ArtsHub

They sit within view of another new work that again draws the racial riot card.

A diptych of large text works: Rush to judgment, white text on a black ground telling the story of the Palm Island riots (2004), and Waltzing Matilda painted black text on white and recalling the Cronulla riots of 2005. It should be remembered that Ah Kee’s first paintings were text works in 1999 – this is where it started for him.

Installation view of Rush to judgement and left Waltzing Matilda at NAS Gallery; photo Artshub

They are dense paintings, both visually and politically, with phrases like “who let the dogs out”, “Abo Boong Coon”, “Mob Violence” and “Love it or fuck off”. Ah Kee made the point that you can still buy t-shirts emblazoned with the tag “Pure Breed Aussie”.

The upper level of the gallery seems to zig-zag or ping-pong across works, threading stories, histories and lives together in a complex narrative. Among the noise is the painting Bad Sing (2011), and while key to Ah Kee’s conversation it feels clumsy, its looming scale like a raw wound against the other more elegant, newer works.

It goes back to where I started. Should we refrain from a critical aesthetic reading in respect of these stories? An artist would always rush to say no. But the message of white guilt leaves little space for dialogue – if anything it is counter intuitive to that message of free speech.

Overall this is a ballsy, probing, and vocal show. It is exquisitely hung and paced, and its wallop is eased by the space for contemplation that the gallery offers. Credit should be given to curator Judith Blackall for that lightness of touch, but also the nudge to draw out questions. It is also a beaut opportunity to see the diversity of Ah Kee’s practice.

The exhibition is part of the Sydney Festival, and while it did not received funding from the mega umbrella event, it did claim the spotlight symbolically launched first in the festival’s program line up by Indigenous Artistic Director Wesley Enoch.

My feeling is that we are getting better in Australia at giving space to mid-career surveys, and better still at talking about them. This is an exhibition that should occupy your dance card during Sydney Festival – and yes, “occupy” was a deliberate word choice.

Read: The soft-glove politics of Indigenous festival programming

RATING: 4.5 out of 5

Vernon Ah Kee: Not an animal or a plant

7 January – 11 March

NAS Gallery, Darlinghurst

Curated by Judith Blackall