Pierre Huyghe, L’Expédition Scintillante, Act 2 (light show), 2002. Collection Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León (MUSAC). Photograph by Marcus J. Leith

Walking though Pierre Huyghe’s show at TarraWarra Museum of Art is to immerse oneself in the non-linear matrix of time, loosening one’s cardinal points in an exhibition whose time-scale spans 30 millions years, between documentation, perception, shifting view-points and discovery.

In a room populated by liberated creatures, spiders and ants erupt from a hole in the wall and erode the invisible conceptual frame that traditionally encases museum artwork. In the same room hangs Untitled #7 Pierre Huyghe, 2008: the first document of the exhibit, consisting of a single sheet, similar in appearance to a dictionary entry. Yet, when reading the listed ‘déclarations’ the veneer of rational orderliness and intelligibility of the page-manifesto disintegrates in a way that is reminiscent of Dada’s collages of meaningfully juxtaposed texts, nonsensical for the purpose of fighting established meanings and culture. Pierre Huyghe is one of the artists partaking in L’Association des Temps Libérés established in 1995.

In 2008, the artist Jorge Pardo invited the Association’s participants to send an image or a text of their choosing for printing in a journal. Out of this collaborative compendium of entries married by chance, Pierre Huyghe extracted Untitled #7: the page defining the purpose of the Association as ‘développement des temps improductifs, pour une réflexion sur le temps libres, et l’élaboration d’une société sans travail.’ One is reminded of Andre Breton’s dislike of a society that is dominated by work and which blocks the individual’s mind from unrestricted intellectual freedom with rational, moral shackles: as Breton affirmed in Nadja (1928) ‘there is no use being alive if one must work. The event from which each of us is entitled to expect the revelation of his own life’s meaning – that event which I may not yet have found, but on whose path I seek myself – is not earned by work.’ Breton’s illumination was realised by night, through dreams and the unconscious; similarly the paragraph defining the Association’s belief in ‘freed time’ in Pierre Huyghe’s Untitled #7 is significantly ‘visible only under black light, a form of illumination found most frequently in night clubs’ in the words of curators Amelia Barikin and Victoria Lynn.

The exhibition is about a mode of time travelling, which, in effect, generates a mind travelling experience for the viewer, therefore, freedom. Time-boundaries are defeated and extended beyond conceptual and material frames. The viewer’s encounters with the video artworks, 3D pieces and live creatures constantly present a surprise element; in fact the exhibit is rich with Duchampian trebuchet: a trap to generate an epiphany in the viewer. The Crystal Cave (Sleeping), 2009 piece shows a three-dimensional cave of wonders saturated by coalesced and mineral slabs similar to a ruined colonnade or a glowing spider web. The artist is asleep in the cave, his head against a pillow and his body resting on an iridescent bed. The image seems fictional, perhaps a clever deceit ordained by the help of digital-art mastery. Trebuchet! The photograph is one of two pictures that document the artist’s journey in 2008 to the Naica Mine cave in Mexico three hundred meters below the ground. The viewer is left wondering at the nature of the artist’s dreams in a cave where reality and surreality meet.

The film artwork De-extintion, 2014 extends the time scale within the microscopic realm, so that in the viewer’s imagination the limitlessness of space is conceptualised both in terms of galactic magnitude as well as irreducible microscopic immensity. Huyghe used scientific cameras to capture the crystallised life of a 30 million year old fragment of amber. Bubbles of air transform into suspended planets and the perlaceous, liquid blue of an insect’s eye metamorphoses into a nebula. High frequency clicks and hisses deceive the ear as if they were the extinct voices of the two insects copulating in amber, but in fact they are the mechanical sonance emitted by the moving camera. De-extintion closes the gap between life and death through a visual voyage of discovery observing the time-frozen bodies of ancient insects in a film whose golden tones utterly seduce the eye.

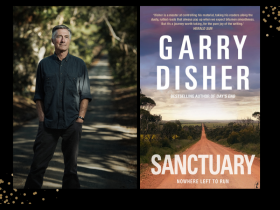

The film-artwork A Journey That Wasn’t (2005) documents the artist’s quest for a new territory, an uncharted island off the coast of Antarctica. The viewer imagines that the film must be a staged and speculative journey, but when exiting the projection room one is faced with a document certifying Huyghe’s actual discovery of ‘Isla Ociosidad’ (Idleness Island). In the same projection-room a light box begins to emit flowing vapours that are illuminated by shot-coloured lights, which fuse with the fumes and music. Out of this amorphic vision one starts to imagine the silhouette of the ‘Isla Ociosidad’ and begins to entertain ideas about the beginning of time and the immaterial conception of this speculative journey in the mind of the artist. Hence, L’expédition Scintillante, Act 2: Untitled (light Box), 2002 is the very essence of the creative process and its immateriality is singled out against the documentary reality of its counterpart film A Journey That Wasn’t, 2005.

In an exhibition that focused on extending time and discoveries one would expect a cognitive purpose to this scientific and artistic expedition, yet Huyghe plays another trebuchet: the artist calls ‘no knowledge zones’. Knowledge and rationality are not the aim of Huyghe’s journey, in fact the journey has no aim, no finalism: in the artist’s own words, ‘as I start a project, I always need to create a world. Then I want to enter this world and my walk through this world is the work.’ Huyghe’s exhibition is one without confines. Walking through the rooms that project the video artworks is to navigate an evolving super-organism, constantly generating itself as the projectors continue playing Huyghe’s liberation of ‘freed time’.

Rating: 4 stars out of 5

Pierre Huyghe – TarraWarra International 2015

Curated by Amelia Barikin and Victoria Lynn

TarraWarra Museum of Art

29 August – 22 November 201