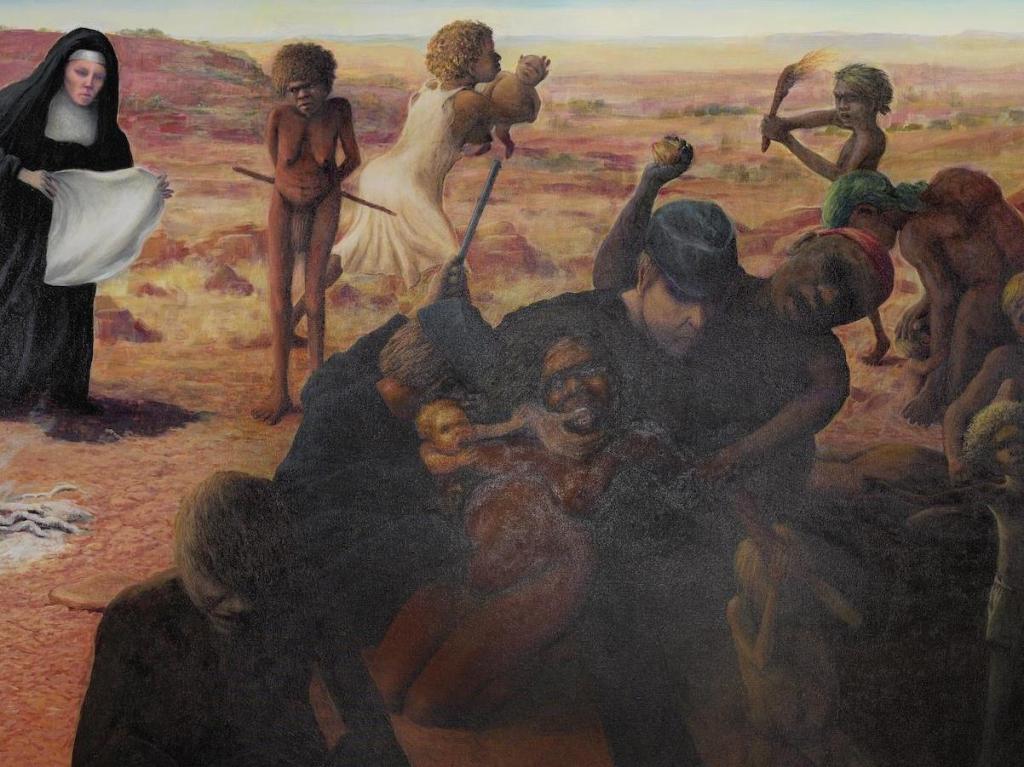

Detail of Harold Thomas’ winning painting Tribal abduction; courtesy the artist and MAGNT

Last week, Harold Thomas was named winner of the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards (NATSIAA) for a painting that cuts to the core of the Stolen Generation story.

He told ArtsHub: ‘Some people were shocked and they had to reorganise their thoughts and come back to take a second look.’

Dominating a group of figures is a woman whose child has been torn from her breast by the authorities. Titled Tribal abduction, the judges described Thomas’ painting as ‘a raw truth which provides space for cathartic reflection’. The panel included Vernon Ah Kee, respected contemporary artist, Kimberley Moulton, Senior Curator, South Eastern Australia Aboriginal Collections, Museum Victoria and Don Whyte, Don Whyte Framing,

It is not the kind of painting that we have been nurtured to expect from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists by an art market that has been built upon dot paintings and Dreamings.

Thomas put it simply: ‘Attitudes have changed.’

And, the Telstra NATSIAA has come in sync with that shift of focus.

‘It took 33 years to get their act together. Now it’s like nothing else; there’s such a wide range of work, from desert art to very contemporary stuff. It’s doing its job I think,’ said Thomas.

A Luritja and Wambai man, aged 69, Thomas knows that journey well. He was a finalist in the first NATSIAA in 1984, then known as the Aboriginal Art Award, with what he described as a ‘conservative painting’ on paperbark from his wife’s country.

Then he took home $500 for coming second; last week it was a $50,000 first prize, testament to the value placed today on this important national survey of Indigenous art practice.

Stories that need to be told

Thomas told ArtsHub: ‘Throughout the years the Award provided an opening for so called traditional artists – sand painting and bark painting – to be looked upon as Fine Art, and they succeeded in doing that. But over a time you thought, “What else is there that needs to be conveyed?”’

Thomas knows all about the power of art and its impact. His best known work is the design of the Aboriginal flag in 1971. He is also known for his commercial market in watercolour landscapes.

But winning (NATSIAA) with a highly political painting has been massive for him.

‘For me winning was a change of everything – time to say farewell to Hans Heysen and Albert Namatjira,’ he laughed.

‘You have to be honest and have the courage to prove to world, as well as to yourself, you can do it.’

‘People criticise you and push you back and you can just drown. You have to work hard and keep persisting – to do the journey – and one day you may chose a good painting,’ said Thomas.

Thomas, himself a victim of the Stolen Generation, believes the key is painting what you know.

‘You can see what you want in this painting, there are many overlays but essentially it is about the removal of children, which is universal story today with refugees housed in detention centres.’

‘It is a reminder how you treat them when you remove them. Just like Dylan Voller, you may well be naughty boys but you don’t treat them as if they are terrorists.’

To tell this story Thomas returned to influences from his art school days – the great humanist masters Delacroix, Gericault and Caravaggio – blending that heroism with his background as an activist.

An award that gives art a voice

Thomas said NATSIAA offers a platform to raise issues. ‘It’s not just the art you see on walls. It is a way for Aboriginal people to use art as a voice.’

Luke Scholes, Curator Aboriginal Art and Material Culture at MAGNT, said, ‘Such is the success and longevity of this award, it can now lay claim to having schooled a generation of observers who annually flock to the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT) to immerse themselves in the best contemporary Indigenous art of the previous twelve months.’

The legacy that MAGNT has built over the past 33 years is one of understanding. Now it is shaping a new future.

MAGNT has been growing its Indigenous Collection and recently employed a Curator of Aboriginal Art. It has expanded the geographic footprint of the Award, its public programming and youth component.

In 2014 the Telstra Youth Award was introduced, joining five other prize categories. Scholes explained: ‘It’s an investment that will keep NATSIAA relevant for decades to come. Its inclusion embraces innovation and changing trends in the contemporary Indigenous art market.’

The new look plan is working. Seventy-five artists from 244 entries were selected as finalists this year.

Thomas encourages young artists to give the award a go. ‘I am not the person who enters competitions. They piss me off that they judge your painting better than another, but this time round it was different.’

Director MAGNT, Marcus Schutenko said NATSIAA was important for artists’ careers. ‘Art awards exist to promote the best art being produced in these times as well as to encourage emerging artists to develop their work and careers. They also encourage artists who may not be participating in the market to showcase their works to their peers.’

Scholes added that this award also helps the broader Indigenous discourse. ‘In the process, our knowledge of Australia’s rich Indigenous cultural heritage has broadened, so too our exposure to contemporary concepts of Indigenous identity, relationships to land and Indigenous peoples’ ongoing struggle for recognition.’

The power of education

Thomas won a scholarship to the South Australian School of Art at 17. He went on to become the first Aboriginal to graduate from an Australian art school and then the first Aboriginal to be employed in a State Museum – the South Australian Museum.

Later he completed an Honours degree in Social Anthropology from Adelaide University, where he became involved in the Civil Rights Movement. It was then that an exhibition of Oceanic art at the Art Gallery of South Australia got his ire through its exclusion of Australian Aboriginal art.

Thomson curated An Exhibition in Protest at the South Australian School of Art, which included many different artists from the Top End and Central Australia. This was the first exhibition to show Aboriginal art only. It was 1972.

In many ways that point of activism, visibility, diversity and celebration is the genesis of what the Telstra NATSIAA and MAGNT are achieving today.

The 33rd Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards is on show at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory in Darwin, 5 August – 30 October.

Entries for the 34th Telstra NATSIAAwill open early-2017, with the prize scheduled for August to coincide with the Darwin Festival, Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair and National Indigenous Music Awards.