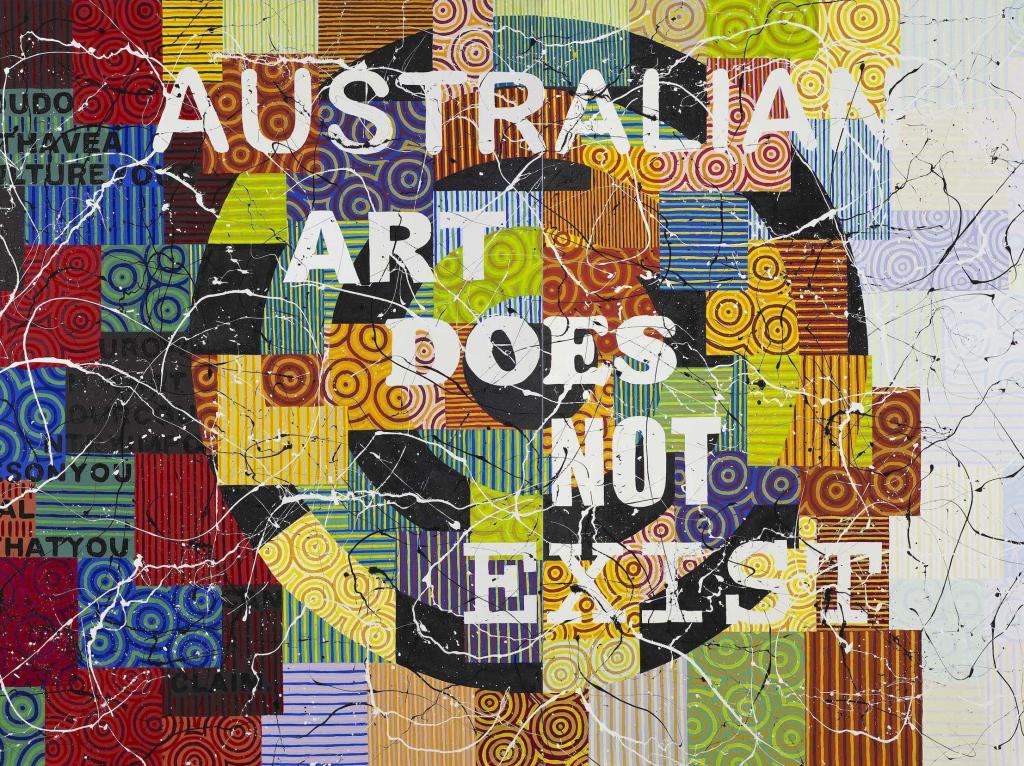

Richard Bell, Judgement Day (Bell’s Theorem) Detail (2007); Colleciton QAGOMA, courtesy the artist.

It has been a long time

Gallery Director Chris Saines said that the rooms were previously designed for the temporary exhibition, Masterpieces of the Prado, which came to the Gallery in 2011. ‘It was more than time. We took the opportunity to really rethink – to reimagine – what those Australian Galleries could be,’ he said.

Part of that reimagining has been to return the galleries to the original vision of architect Robin Gibson AO. ‘We’ve opened up windows, removed many temporary walls, and created new exhibition display furnishings and seating to complement Gibson’s design,’ said Saines.

A particularly nice touch is the ability for the public to peer down into the galleries from the “whale mall”, a pedestrian thoroughfare between QAG and the adjacent natural history museum.

This metaphorical as well as actual pointing to the past, and a lofty view from

‘We have presented a very exciting rethinking of the way in which we interweave and interlock the stories of Indigenous Australian art history and non-Indigenous or post

‘We have really rethought what Australian art is and what it consists of.’

Dr Kyla McFarlane, Acting Curatorial Manager, Australian, who headed the rehang team, added: ‘It is all about really owning that approach; Chris is really proud that we have bought the Indigenous art collection and the Contemporary collection into that presentation of Australian art.

For the past

QAG is not alone in this. State galleries have had to find their own point of difference and definition, which has got somewhat lost in the last 20 years with the emergence of the new contemporary art venue. What these recent rehangs have done is force our state galleries to go back and rethink how they connect with people in our times.

Torres Strait artist Alick Tipoti’s newly ommissioned wall mural Kudursur (2017) – a painting about summoning the winds to blow – juxtaposed with Gordon Bennett’s portrait of Eddie Mabo; installation view Australian Art Collection hang at QAG; Photo Artshub

Re-boost or responsibility?

There is great responsibility in hanging a collection of Australian art in a state art gallery. For many visitors, it might be the first introduction that they have to Australian art, especially if visiting from another country, so getting that story right is critical.

And at a local level, it is hoped such a collection will open the door to the narratives and nuances that are particular to an individual state. After all, the collecting habits, patronage and artistic influences of Victoria, for example, are extremely different from those of Western Australia or Queensland.

And yet it is surprising how wrong state art museums have got that narrative in the past, traditionally rolling out heavily chronological hangs that were largely locked into a colonialist read of art history – a story of power rather than

QAG’s re-hang is the latest to have happened across curatorial circles. It follows, most recently, the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) and the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA), each very differently toned.

Two-thirds of the total QAG collection is focused on Australian art. ‘We wanted to really focus on the things we could tell really well,’ McFarlane told ArtsHub.

‘We wanted to bring together favourites in a different context so that they were talking about the collection from where we stand – that is, the state of Queensland – and to bring into sharper focus this idea of contact.’

She continued: ‘We were really keen to bookend the hang with Indigenous stories and pare back a refined representation of the landscape, adding to those collection jewels – the Conrad Martins and Von

What is being described as a loosely chronological spine runs the entire length of the gallery, with a progression of break-away rooms with Queensland themes, which encourage a meandering experience.

‘We’ve been able to tell a far more organic story of the collection,’ said Saines.

Moving through the rooms those themes look at: first contact and immigration; the Brisbane River to Morton Bay and Fraser Island; the strong holdings of Ian Fairweather but from the new perspective of Macassan contact of South Sulawesi; the grating disparities between the history of women’s labour and leisure; a debunked rethinking of the notion of the “tropical”; the history of labour and industry particular to Queensland; using The Field exhibition as a breakaway moment to Australian abstraction, and finishing with a suite of Central Desert paintings that use the backdrop of Richard Bell’s painting, Judgement Day (Bell’s Theorem) (2008), which is emblazoned with the slogan “Australian art does not exist”.

‘Everything you see we have thought about; we have thoroughly planned the way that works are seen against other works,’ said Saines.

McFarlane added: ‘It is not just about the strength of our holdings – such as Sidney Nolan’s works about Fraser Island – rather it is about telling our history. While it is about audiences, it is also about us having a pride in that as well.’

Velvet glove delivers powerful wallop

What is traditionally known as the “history wars” – an Australian narrative told from a disparate white and black lens – takes on new importance within the context of the QAG re-hang of its Australian Art Collection.

Saines said: ‘We have worked to re-engage the display of

Perhaps these pairing of artworks best

Judy Watson’s Sacred Ground Beating Heart (1989) and a work from 1991 by Gordon Bennett, which both talk about

In a curious grouping in that same room, William Dobell’s painting The Cypriot (194) is paired with Michael Zavros’ self-portrait Bad Dad (2013), two immigrants adding a subtle conversation about the idea that we are all visitors to this land.

Continuing that potent juxtapositions is Daniel Boyd’s new painting Untitled (HNDFWMIAFN) (2017) is positioned beside Margaret Olley’s painting The Banana Cutters (1963) to question the written history of labour in Queensland.

Similarly, Tracey Moffatt and Gary Hillberg’s video Other (2009) on a wall salon hung with works by Ray Cooke, Margaret Olley and others that question the exoticising of culture, race and place, in the section Tropical.

Section titled Tropical debunks stereotypes of the “garden of Eden” view of Queensland; and in the background Helen Johnson’s new commission that speaks of women and labour. Photo ArtsHub.

Video still Tracey Moffatt and Gary Hillberg’s work Other; Collection QAGOMA

Putting living artists first with commissions

The gallery has commissioned major new works by Daniel Boyd, Sonja Carmichael, Dale Harding, TSI artist Alick Tipoti – and the only non-Indigenous artist, Helen Johnson – to inaugurate its new hang of Australian art.

Positioned at the starting point to this new narrative of Australian art is Queensland born Aboriginal artist Dale Harding. He has just returned from representing Australia at the important international exhibition Documenta.

His site-specific work, Wall Composition in Rickitts Blue (2017), plays with the language of stenciling – the hand in traditional rock painting replaced by shovel for contemporary labour. His use of laundry power Ricketts Blue, popular in colonial times to “brighten whites”, is used as a symbol for the domestic labour that generations of his female ancestors were forced into through government policy.

Dale Harding installing his new commission Wall Composition in Rickitt’s Blue (2017) at QAG; Photo courtesy the artist and QAG

He said this work had many departure and entry points. ‘Rickitts blue became a material – a colour and movement of its time – and is an important touchstone that speaks to ideas of contact and first trades and exchanges. While it was a laundry powder that was introduced to the colonial frontier, it was incorporated into daily ceremonial life and used to decorate boomerangs and shields,’ said Harding.

Daniel Boyd has worked from an archival photograph to paint a powerful work that fills a gap in the gallery’s collection with regard to the history of indentured labour in Queensland.

‘Daniel Boyd really created for us what is the first painting in the collection that deals with one of the most difficult and stained pasts of Queensland history,’ said Saines.

Boyd told ArtsHub: ‘The reason I chose that image is

‘It is great to see the complex relationships that play out in the space. It puts things in front of people that they wouldn’t necessarily want to deal with, or understand, as it will challenge their being. It is about respect; it is really refreshing,’ he told ArtsHub.

Torres Strait Island artist Alick Tipoti is also represented by a commissioned wall mural, is paired with a portrait of land rights activist Eddie Mabo, painted by Gordon Bennett, while local Stradbroke Island artist Sonja Carmichael’s newly commissioned collection of woven baskets is paired beautifully with traditional fish traps by Jack Moranbarra, which seemingly levitate in conversation over the commission. Again playing past and present, tradition and contemporary conversations – Carmichael repurposes materials washed up on the beach.

The verdict

The pairings across this collection re-hang encourage viewers to dig deep. Simply, this is a hang that “encourages” you to return. You feel slightly overwhelmed at moments. Partly that is this ricochet between ideas – big ideas that need time to digest; to rethink a “known” history – but also the sense of pace that this

I am not sure how alert that pace was to the way in which audiences read today, a society that moves through things in quick bites and selfie moments. But there is a sense that once gorged on, this visual feast, like a full belly, lingers. And, as it dissipates with time,

Perhaps this equates to a successful collection hang. QAGs Australian art rehang will be up for a number of years, and will clearly continue to satiate viewers with its intriguing nuances. Afterall, the history of Australian art has been fabricated over 200 years; to unpick it is going to take a little time.

QAG’s Australian Art Collection is on show daily in the Josephine Ulrick and Win Schubert Galleries and is free to view. The Queensland Art Gallery is located in South Brisbane.