Ephemeral by nature, street art may be tagged over, demolished or simply fade with time. We might notice a particular piece on our daily commute, or when we walk around the neighbourhood. There’s no telling how long a work will remain intact, but the blow is often delivered when it doesn’t appear as we remember it.

In 1984 New York-based artist Keith Haring flew to Australia for a two-week visit that left an indelible mark on the local art scene. During that time he painted two murals in Melbourne, one in Collingwood, and the second on the National Gallery of Victoria’s (NGV) water wall. The latter was short-lived, lasting only two weeks before a brick was was thrown through the centre, shattering a panel depicting a child’s birth. Theories for its destruction include homophobia – Haring was an out gay artist – cultural appropriation, or an aversion to the birth scene.

That mural was recently recreated for the NGV’s Keith Haring I Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines exhibition to coincide with the 35th anniversary of Haring’s visit.

‘One really significant part of the reason that we put [the mural] up again, was because originally people didn’t really have that much time to appreciate what is an incredible feat that Haring managed to complete in two days,’ said Meg Slater, Assistant Curator at the NGV.

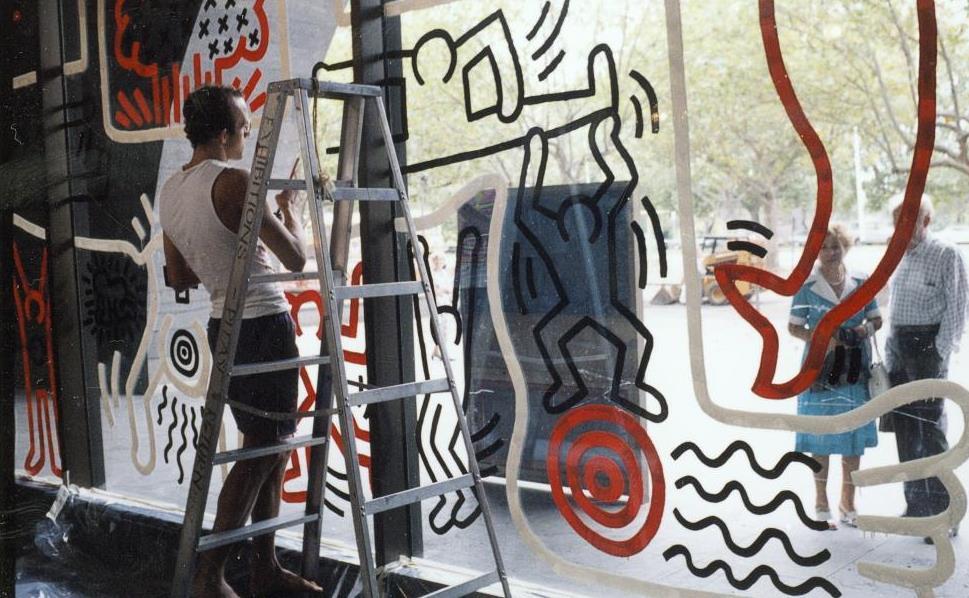

Using three layers of paint and without prior sketches or preparation, Haring wove a series of images across the 20m wall, working from a cherry picker and never once stopping to stand back and check his progress.

At the time, Haring told journalists the mural was: ‘A series of images about life and things which threaten life.’ Both then and now his work his highly relatable, with themes touching on politics, sexuality, the environment, and technology.

Keith Haring’s NGV water wall reimagined for the Keith Haring I Jean-Michael Basquiat: Crossing Lines exhibition. Photo: Eugene Hyland

While the NGV was restaging Haring’s work, another iconic Melbourne mural was also being celebrated, albeit as a virtual tour.

From Bomboniere to Barbed Wire, also known as The Women’s Mural, was painted in 1986 by Megan Evans and Eve Glenn on the wall of the old Gas and Fuel Depot in Smith Street, Fitzroy. Celebrating the diversity of women who lived in Melbourne’s inner north at the time, the mural also offered a response to the large-scale sexist advertising prominent in the surrounding suburbs. For the mural to even exist was a miracle, given the lobbying both women had to undertake to display the work – it took to years to be approved. The questions it raised about women’s visibility are still relevant today.

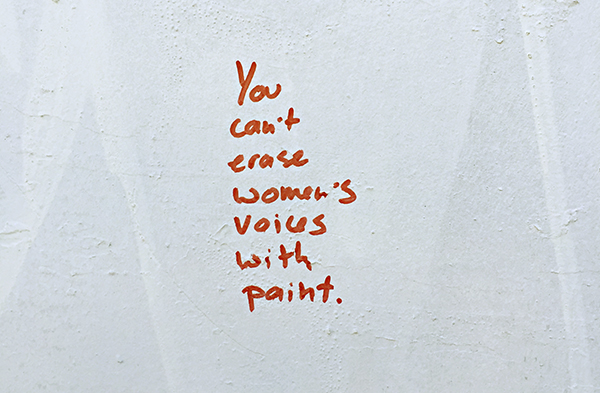

In 2016, the piece was defaced by a notorious tagger, causing widespread community outrage.

‘People were sad and angry because of the silencing of a very visible women’s artwork and thus stymieing their voice,’ said Penelope Lee, Board Director at Her Place Women’s Museum who collaborated with The Women’s Mural Documentation Project to create the virtual tour.

The mural might have been ruined, but the community’s spirit was still intact. Responses to the graffiti were met with messages of defiance written on the wall and the Women’s Mural Documentation Project was formed to document the work. The wall was demolished for a redevelopment of the site in October 2019 and the re-imagined virtual mural was launched soon afterwards.

‘It was really important that that foundational context was put into the digital archive,’ Lee said. ‘Those histories aren’t often preserved because public artwork is ephemeral.’

Eve Glenn (L) and Megan Evans (R) on ladders, moving scaffolding in front of their mural From Bomboniere to Barbed Wire. Image courtesy of Megan Evans Archive, photographer unknown, 1986.

Piecing together a part of history

Re-staging public artworks which have been defaced is a complex process, especially when the work is old, but it’s even more challenging to reconstruct a piece when the artist is no longer alive.

In the case of Haring’s mural, the NGV were lucky to have 60 photographs of the original mural, taken by a former staff member, Geoffrey Burke, in addition to footage from a documentary shot by AFTRS.

‘It was basically quite a painstaking process of overlaying, flattening and manipulating all of the images to ensure we were getting every detail right,’ Slater told ArtsHub. ‘We basically wanted to try and get as close as we could to that original design, but without trying to copycat Haring.’

Created in close consultation with the Keith Haring Foundation in New York, the mural took the form of a vinyl overlay, to be assembled panel by panel. It took two days to construct, the same amount of time it originally took Haring to paint.

Feminist graffiti on the Women’s Mural in reaction to its capping. Image by Colin Mowbray, 2016

Re-imagining the Women’s Mural was also a big project. It involved consultations with the community and the original artists who provided photos which were then digitised to provide an account of the mural throughout its history from 1986 right through to its defacement in 2016.

It’s the first time a mural has been documented as a virtual tour in Victoria and also possibly in Australia.

‘I think the mural has set a benchmark and could be both educational and culturally enriching for audiences,’ Lee said. ‘I think what we’d hate to see is that it replaces the visceral experience of going to a site and seeing a public artwork, but It’s important that it’s there as an adjunct to it.’

Keith Haring / Jean-Michael Basquiat: Crossing Lines is showing at the National Gallery of Victoria until 13 April 2020. The Women’s Mural Documentation Project can be viewed online.