Is the idea of custodianship an expressions of First Nations cultural equity, or yet another imposed white frame to work within? A panel at this week’s AMaGA conference (Australian Museums and Galleries Association) took to the term ‘hammer and nail’.

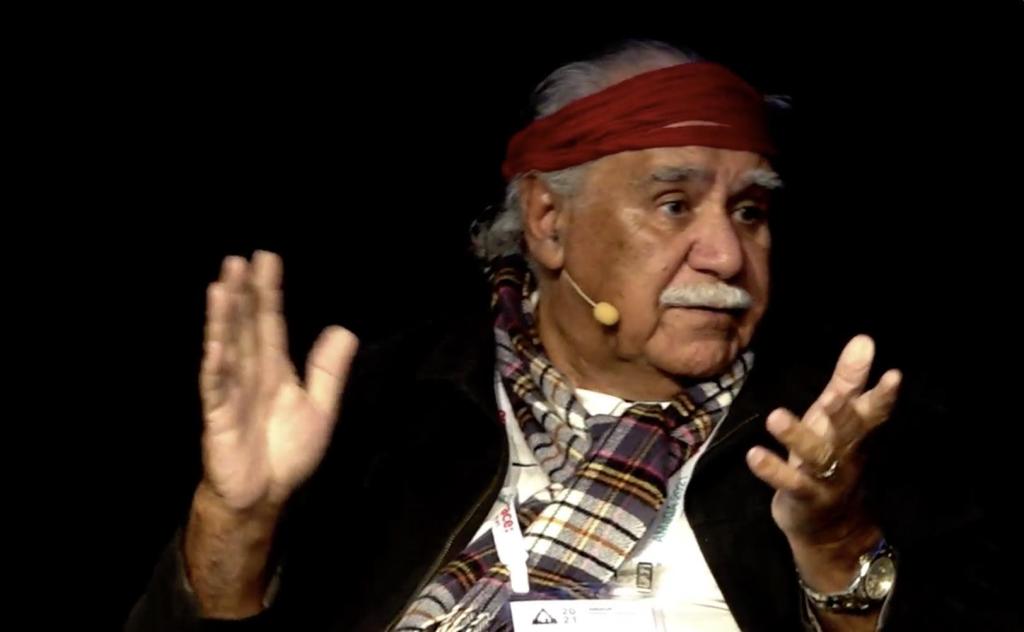

Uncle Michael Ghillar Anderson was one of four men who took the long drive from Country to Canberra to set up the tent embassy outside then Parliament House in 1972. He clearly has following in his footsteps, as part of the diplomatic human rights envoy under Whitlam Government, and today a senior law man.

Uncle told AMaGA delegates he was not fond of the term ‘custodianship’.

‘I have enormous problems with that word – we own our culture, no one else does. I have a trustee relationship with my culture, and an obligation to pass on what has been given to me, and sometimes the museum interferes with that – they are mad on sticks, stones and bones.’

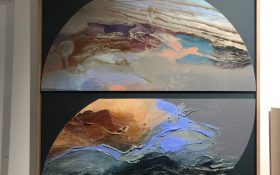

It was a view shared by artist Julie Gogh. ‘I am not a custodian; it is legacy, and my ancestors and family compel me to action.’

Head of Combined Arts at the Council for the Arts, Cara Kirkwood took it further: ‘I don’t like the word traditional either – traditional custodian, traditional art. We are a continuum of a culture from thousands of generations.’

Playing provocateur on the panel, she posed the question to the predominantly white audience: ‘When you use these words, what do they mean?’ She said that it is the same ‘frame’ that we apply to a ceremonial welcome in the workplace. ‘Why are we acknowledging Country? I get tired of rote acknowledgements, and I invite that you never do it again.’

She suggests that when delivering an acknowledgement to country to ‘embed yourself in the place’, she continued, ‘I like to find moments you have found yourself – delight, challenged, curiosity – to add that personal experience and demonstrate your capacity to have connection and insight in to what you are part of, and acknowledging.’

She says this simple idea ‘amplifies and elevates the Indigenous idea of collectivity.’

Uncle took a harder line, but one that stemmed also from the rote disconnection. ‘I tell people they are not welcome to my Country; you have to learn about what happened here before … [so] I tell the story and say let’s get on with business.’

The question of repatriation

Uncle has sat on a UN Committee in Geneva to discuss the repatriation of cultural material around the world.

‘The material culture collected is mistakenly identified as relic of the past – our culture is not a relic,’ he continued: ‘Some Greek and Egyptian people on the panel were arguing with the British that they should return our stuff to us.’

His inference was that it was more about economic and ownership than a discussion about material culture.

He spoke of an important Hermansburg work held in the Strehlow Collection in Adelaide. ‘They [the men] could not do ceremony anymore, because objects been taken from Country; they were the physical evidence of that story and they stropped dancing because it has been taken away.’

‘We found that kangaroo in the basement of the museum at Adelaide University. The old men came down and they sang all night. When they came out in the morning, they were asked, “What do you want us to do with them?” And they said, “They are not good to us now, you can keep em.”’

Uncle explained that the men sang all night to sing out the spirit from the object, and sing it into a drawing, which they then took back to Country and sang it into another object.

‘It is the same when we do art – they sing the spirit into the story when they are painting, and it is vital you do not take that painting,’ he added.

It is an interesting lesson of repatriation and custodianship, and how there is still so much learning required around these areas when it comes to cultural material.

Read: How social justice and a pandemic are shaping Museum leadership

AMaGA First Nations panel (L-R), Nardi Simpson, Cara Kirkwood, Julie Gogh, Michael Ghillar Anderson, Jilda Andrews. Screenshot.

Re-thinking custodial roles

Cara Kirkwood was the first First Nations person appointed to the Art Gallery of South Australia, and now at the Australia Council, is a national advocator and influencer for the bridge that education provides between indigenous and non-indigenous communities.

‘The Aboriginal world view is very 360, and so dimensional that Western structures can’t get their head around,’ said Kirkwood. ‘The point is in a black world view nothing is independent of the other thing; everything is connected. [So] in trying to affect change we need all sectors to de-silo.’

She continued: ‘We don’t have a shared language on how to create change.’

To illustrate the point Uncle Ghillar spoke of the removal of ancient trees from his father’s Country.

‘They come from celestial law – you call it canon law – our etchings on rocks and those trees are canon law for us – they come from the creation. And so museums have these things, and you have no idea what you have. Part of problem is you don’t know how to read them; you see all these nice patterns and you just see them as a relic of the past. But to us they are the present.’

‘We are very different in cultural thinking; Australia’s got a long way to go in understanding us.’

Uncle Michael Ghillar Anderson

Kirkwood said that one of the problems is fear and failure. ‘In the context of what it is that power fears, in their relationship to First Nations culture and First Nations people, is a white fear of failing.’

‘People are scared of cultural faux pas – black fellas make mistakes too – we have to keep leaning, and it is this capacity to learn as Aboriginal people that we should be really proud of. But all that energy around failure is exhausting,’ she continued.

What can I do?

Kirkwood says its simple: ‘Put it in your budget lines – put cultural competency in your budget lines so you can pay for a nice morning teas with Aunties and Uncles.’

‘First Nations and our culturally diverse mob feel they have no decision making capacity in the arts and culture sector,’ said Kirkwood. ‘If there is one premise I invite is think around the idea of collectivity – stand aside and share power.’

She also said that you need to ‘call shit out at the family BBQ – that is, what it’s like being Black in a white fellas system.’

Uncle Ghillar had the last word. ‘For me it is familiarising yourself with what is here and know what you have – and if not, reach out. Half of you wouldn’t have a clue what you are looking at. It is just a matter of going out and finding information.’

The implication is that we all need to ask a lot more, and ascribe and tell a lot less.

Uncle Ghillar, Cara Kirkwood and Julie Gogh were joined on the panel by author and music director Nardi Simpson (Stiff Gins), which was moderated by Jilda Andrews. AMaGA conference was held in Canberra 7-10 June 2021.