Contemporary art elicits a wide range of reactions. While some people will assert that a work is ground breaking or thought provoking, others will just as readily dismiss it as being too mainstream or a case of the emperor’s new clothes, or something that their child could have done. The one point of consensus seems to be that contemporary art can make money and lots of it, although this money-making capacity is often seen to have a deleterious effect on the quality of work produced.

When the term contemporary art is mentioned, our thoughts tend to gravitate to the upper echelons of the market, where wealthy collectors spend millions vying for examples by a select group of recognised artists. For some reason, we tend not to think of the vast majority of contemporary creative practitioners who work in makeshift studio spaces and struggle to earn a minimum wage. But then again, art is all about the market isn’t it? Or is it?This is the territory in which we found ourselves at the recent Critical Animals Creative Research Symposium, which is held annually as a part of the This Is Not Art Festival in Newcastle. Critical Animals aims to ‘explore opposites and juxtapositions’ and the recent seminar ‘Who Killed the Avant Garde: Apathy and Contemporary Art’ did just that, although in some cases this was notably more successful than others.

The session began with an extremely well-researched and informative paper by artist, arts writer and COFA Master’s student, Sabrina Sokalik, who traced the growing disenchantment with contemporary art in some quarters and the deflation of the art market in a post GFC world. However, those of us whose thoughts didn’t immediately gravitate to the upper echelons of the art market were slightly bemused until it became clear that this was the sector of the market to which she was referring.Sokalik cited recent defectors from the contemporary art scene, including art market analyst and author, Sarah Thornton, and American art critic, Dave Hickey. In her 2012 article, Top 10 Reasons Not to Write about the Art Market, Thornton announced her decision to stop reporting on the art market, because of the predictable and repetitive nature of art market analysis, while Hickey retired last year from an art world which he said had become ‘calcified, self-reverential and a hostage to rich collectors who have no respect for what they are doing.’

Sokalik then turned to Hughes’ seminal essay ‘Art & Money’ in order to locate the source of the art market’s issues with money. It’s not the first time recently that I’ve heard Hughes’ name invoked with regard to the influence of commerce on art. As Sokalik notes, his argument that ‘The idea that money, patronage, and trade automatically corrupt the wells of imagination is a pious fiction’ and that the problem is located more in the ‘emblematic’ power of the prices, has held up rather well.However, as Sokalik acknowledges, money doesn’t answer all of the artist’s problems, because with money comes compromise, particularly as injections of corporate funds are becoming increasingly important in the cash-strapped arts sector where most of contemporary arts practitioners reside (as opposed to the ones in the upper echelons of the market who seem to be rolling in it).

Sokalik’s research was far ranging and her arguments were compelling and one could not reasonably expect to cover the entire gamut of such a broad subject in one paper. However, I would suggest that the issue could be further qualified by addressing not just how people’s attitudes to art have changed, but how their attitudes to money have changed.Depending on their inclinations, people used to worry or brag about how much money they had, but somewhere in the last decade or so people began to use terms such as ‘personal wealth’ and articles in newspapers and magazines shifted from discussing real estate as an investment to considering shares and even art as investment opportunities. It’s one of those chicken and egg conundrums, but there’s certainly room to explore the relationship between the power of the media and attitudes to money when looking at the growth of the art market in the last 50 years or so.

The next speaker was Lucy Randall, Director of Seen & Heard Film Festival, which showcases films by women. As opposed to Sokalik’s global focus, Randall’s talk consisted of observations regarding events closer to home. Randall began by noting the success of the recent Sydney Contemporary art fair and commented that we should be grateful that wealthy art dealers are bridging the gap between local and international markets.She mentioned a newspaper article from earlier this year stating that a former gallery owner and employee of Sydney Contemporary owed some tens of thousands of dollars to artists he once represented. At the time Sydney Contemporary founder Tim Etchells acknowledged that the employee had ‘outstanding debts with artists he incurred prior to joining the team at Sydney Contemporary.’ However, Randall did not mention that Etchells had made it ‘a condition of his ongoing employment’ that the employee submit a ‘detailed repayment plan.’

Randall claimed ArtsHub did not report the incident, ‘because it was not in their best interests’ due to revenue gained from the event.

The Editor of ArtsHub, Deborah Stone, said Randall’s claim was incorrect. ‘We covered Sydney Contemporary as a news event and Sydney Contemporary also advertised with us. We try to be comprehensive but we do miss stories through lack of resources or editorial judgements that decide other stories are more important. We don’t miss them through fear or favour.’Arts organisations and the media are currently undergoing huge changes and staff are increasingly overstretched in an attempt to keep up with the vast amounts of information available. Given this environment, oversight is just as likely as deliberate omission.

In her talk, Randall noted that she used to avoid partnerships, but concedes that over time she’s made inch by inch compromises, because she eventually wants to pay the artists who work with her. Let’s hope that those compromises aren’t misconstrued as moral omissions.

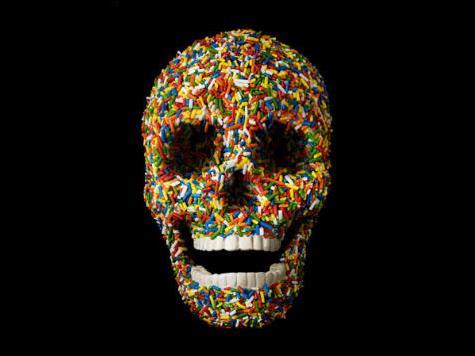

Image: Damien Hirst’s Skulls are among the most valuable contemporary art works.