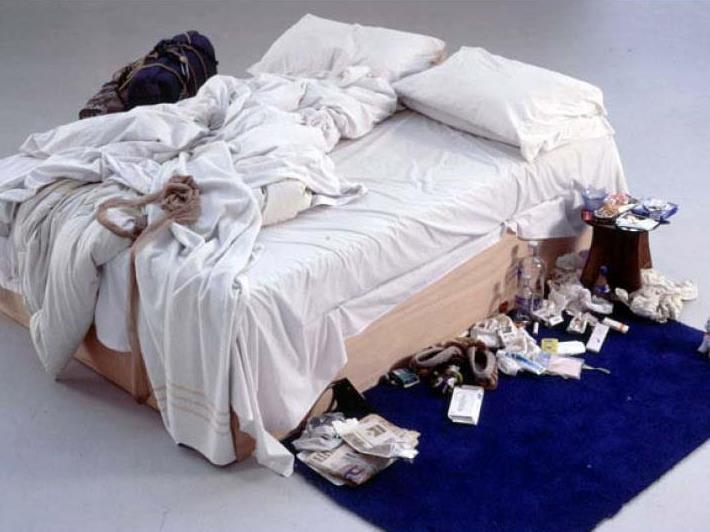

Tracey Emin’s slept in bed was perhaps the most controversial prize winning artwork globally, but it bought huge crowds into the Tate and sold for a motza at auction, so is controversy good news after all?

Last week the winners of two art prizes made the headlines. However, it was not the usual news story of their win that drew the spotlight, rather it was adverse comments from others.

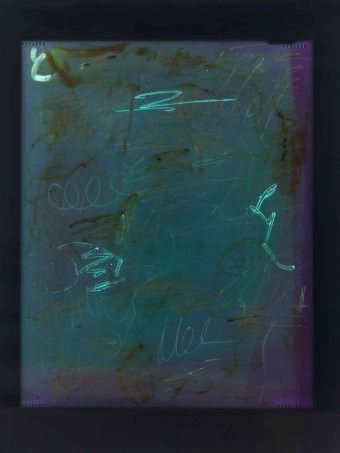

Winner of the 2017 Olive Cotton Award, Justine Varga has been the target of criticism for her photographic portrait, Maternal Line. It is an image constructed from her grandmother’s pen scrawls and streaks of her saliva; it has no bodily representation (in a traditional sense), nor uses a camera. So should it have won?

‘For me when I look at that I have a direct connection to my grandmother, the person rather than the exterior of the person.’ Varga told the ABC.

Justine Varga, Maternal Line 2017; chromogenic hand printed photograph from 5 x 5 inch negative; Acquired as the Winner of the Olive Cotton Award for photographic portraiture, 2017; courtesy of the artist and Hugo Michell Gallery, Adelaide

Prize judge Dr Shaune Lakin, a senior curator of photography at the National Gallery of Australia, has received hate mail and criticism. He told the ABC: ‘I have received really nasty feedback from photographers, but a lot of vitriolic commentary that has come back to me has suggested that the decision was really just about creating controversy. It really does diminish what, for me, was a very complicated and complex process that I took very seriously.’

Larkin added that Varga’s work speaks about portraiture today.

While he said the running commentary of hate mail ‘disrespected’ the artist, it was actually another artist who targeted 2017 Archibald Prize winner Mitch Cairns.

‘I think it’s the worst decision I’ve ever seen,’ said 89-year-old former Archibald winner and three-time judge, John Olsen.

‘It’s entirely surface, the drawing is just not there, and the structure, which is a summation of what makes a thing good, isn’t there,’ he told the Sydney Morning Herald.

Olsen said Cairns’ painting lacked the ‘insight’ of a good portrait and, yet, the portrait was of the most intimate of relationships – that between a husband and wife. Perhaps Olsen just didn’t like the style, or that a younger guard had grabbed the prize, but is that grounds for such public criticism?

Varga told the SMH that she ‘could feel it in the room that people weren’t happy about it,’ when she was announced the winner of the Olive Cotton Award.

Olsen continued his attack, turning to 2017 Wynne Prize winner, Indigenous artist Betty Kuntiwa Pumani’s Antara. He questioned whether it was a landscape painting. ‘If one considered paintings by [Elioth] Gruner or [Brett] Whiteley, there’s a sense of place in it,’ he told SMH, adding that the winning painting existed in ‘a cloud cuckoo land.’

Olsen has won the Wynne twice, and felt ‘compelled’ to speak out.

Blogger and former Art Gallery of NSW Society (AGS) employee, Judith White reminded that Olsen ‘first came to public prominence back in 1952, as a leader of art students protesting against the conservative Archibald Prize choices of the Art Gallery of New South Wales Board of Trustees. The winning portrait that year was by William Dargie.

‘That’s him on the left of the picture: “Archibald decision death to art” reads his placard,’ White points out.

Perhaps criticism is ok only when its not pointed at you?

But has much changed? Writer Garry Maddox reminds us: ‘The Archibald has long been a circus, and controversy is good publicity for it.’

Criticism, court and crowds

Whether Varga’s photograph is a portrait or not, and Cairns’ painting is good or bad is irrelevant at the end of the day.

The galleries are delighted with the attention and the ensuing foot traffic, and for the artists, the prize money and career accolade long outlasts the fiery moment of criticism.

Or does it? The Turner Prize in the UK is a good example.

It’s a little hard not to be aware of the controversy and criticism generated by the work of Tracey Emin (1999 Turner Winner) with her installation, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995.

Her piece caused a media storm and saw attendance rise to a record 140,000, with an average 2,000 visitors a day. Indeed, it caused such controversy that British Culture Secretary Chris Smith criticised the jury for deliberately selecting shock installations that gave the country a bad name abroad.

Or how about 1998 Turner Winner Chris Ofili, with his portrait of a black Virgin Mary made from elephant dung? An illustrator protested against his work by depositing dung on the steps of the Tate. The work’s fame increased when presented the following year at the Brooklyn Museum in the YBA (Young British Artists) Sensation exhibition; later it sold at auction for US $4.6 million.

And then there’s Damien Hirst’s now infamous tiger shark encased in formaldehyde – these art prize controversies have resulted in the artists becoming globally recognised household names. What more could an artist want?

We step a back a bit further, to Marcel Duchamp’s famous Fountain (1917), his readymade pissoir. It was promptly excluded from the Society of Independent Artists’ inaugural exhibition – we are talking Archi-level fame here – and Duchamp, in protest, resigned from their board.

The thing all these winning works have in common is that they challenge the status quo. People don’t like change. And people love to have a gripe. It is the perfect recipe for drawing crowds.

How does Australia fair – the country that has the most art prizes in the world? As early as 1923 – the Archi only started in 1921 – WB McInnes’ winning Portrait of a lady was criticised as the sitter was not named and it was therefore impossible to determine if the work met the condition of the prize.

But it was William Dobell’s win, with a portrait of Joshua Smith in 1943, that was the real start to the pairing of art prizes and controversy.

When the award was announced, two other entrants, Mary Edwards and Joseph Wolinski, took legal action against Dobell and the trustees, on the grounds that the painting had not met the prize criteria of a portrait.

The case was heard in the Supreme Court of NSW and was dismissed; following came an appeal and an unsuccessful demand to the Equity Court to restrain the claimant to pay costs for Dobell and the trustees.

Other works that presented challenges, criticism and controversy over the years include: John Bloomfield’s portrait of filmmaker Tim Burstall, which was disqualified in 1975 for being painted from a photo; Brett Whiteley’s Self Portrait in the studio in 1976 – again a benchmark in moving on from traditional conventions; Bloomfield struck back in 1981 when he threatened legal action over that year’s winning portrait of Rudy Komon by Eric Smith, which strongly resembled a 1974 photograph of Komon.

Then there was Adam Cullen’s winning work in 2000 of actor David Wenham that used house paint and was criticised as ‘simplistic, crude and adolescent’. Cullen was also criticised for glorifying a crime figure when he chose to paint Mark ‘Chopper’ Reed; and in 2004 Tony Johansen took the Art Gallery of NSW to court over Craig Ruddy’s winning portrait of David Gulpilil, as it was made with charcoal. Two years later the Supreme Court dismissed the case.

So much bitterness and pettiness; so much public spotlight and increased attendance.

The Archi – while the most contested – is not the only Prize to be targeted. The Australian’s art critic Christopher Allen resigned from the Blake judging panel over the inclusion of Adam Cullen’s lurid depiction of the crucifixion of Christ in 2008.

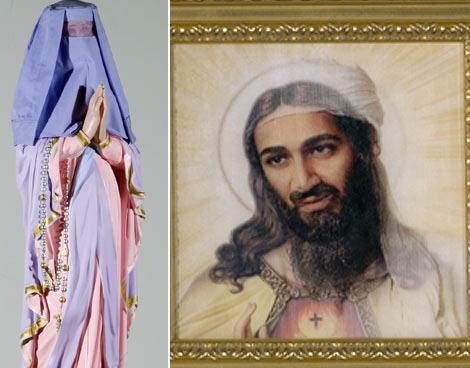

And in 2007, Prime Minister John Howard described a work by Blake Prize finalist, Luke Sullivan, as ‘gratuitously offensive’. It was a statue of the Virgin Mary shrouded in a burqa.

Another artwork that year, Priscilla Bracks’ holographic image of Osama bin Laden that morphed into an image of Jesus Christ, was also targeted for comment. Bracks denied she had deliberately set out to be offensive.

The Australian Federation of Islamic Councils’ president Ikebal Patel said the statue was ‘not at all offensive’, because both the Virgin Mary and Jesus were revered figures in Islam. He continued: [Mary wearing a burqa is] no different to how our mothers and sisters are expected to be modest in their dressing,’ but said he was ‘affronted’ by the bin Laden holograph.

The Anglican Bishop of South Sydney, Robert Forsyth, told media: ‘Christians ought to be cautious about “running to the press” to complain about being offended … You need to limit the language of outrage to things that are really outrageous.’

Perhaps this is the crux of this debate. In our climate of social media and free-for-all commentary we have lost judgement in knowing when to speak out and when to hold those comments back for private discussion.

Earlier this month, fellow ArtsHub journalist Richard Watts published the article, Freeing the arts from the yoke of neoliberalism, describing a market-driven world of winners and losers which prioritises ticket sales, visitor numbers and profits over creativity.

Artist Michael Zavros suggests that, ‘For whatever reason, art prizes are an integral part of the art system … [and] are at the mercy of the judge and their politics, their desires, their taste and aesthetic preferences.’

The bottom line seems to be a flat line. Art prizes are here to stay; Galleries will continue to use them to bolster attendance; and increasingly everyone’s a critic.

Perhaps prize application forms should come with the old fashioned warning once printed on medieval maps – ‘here be dragons’.

The $20,000 Olive Cotton Prize is a a biennial award for photographic portrait hosted by the Tweed Regional Gallery, in northern New South Wales. The $100,000 Archibald is a bastion of the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

The Olive Cotton Prize is showing until 8 October. The Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prizes are on show until 22 October.