The progressive de-emphasis on discovery has made it harder to resist the tide of the bogus, the spurious, and the headline-grabbing but insubstantial claims.

In recent years, in Art History as across the humanities, we have become suspicious of discovery, or even contemptuous of it. We have become more interested in the ‘so what’ than the ‘what’. We are now focused on explaining meaning, context and the relation of an artwork or artist to a set of social and cultural or philosophical currents.

This is perceived as the added value of our discipline, the seat of its intellectual respectability. We have consequently distanced ourselves, gradually, from ‘primary’ matters – of identification and classification.

This shift of course is easy to explain as the necessary act of putting respectable academic distance between a humanities discipline and the murky world of amateur sleuths, dodgy dealers and self-proclaimed experts of the interwar years, the shady attributions, suspect dealers, false provenances and other distasteful commercial practices that could be left to the market.

Of course, art historical discoveries are being made, everywhere, all the time. However, what is interesting is that the thrill of discovery (and the serious business of taking the informed and calculated risk that enables these discoveries) is, it seems to me, being carried on in a variety of spaces outside the Academic discipline of Art History. And, I would argue, this is often to the great detriment of our field.

Even museums, now are hesitant about their discovery mission, given that collections management, storage and the exhibition bandwagon provide enormous challenges and that the skill and manpower needed to make discoveries and rediscoveries is not readily available.

So, actually it is in a loosely conceived ‘private sector’, commercial galleries and dealerships and consultants not to mention into a nether world populated by freelancers of various degrees of skill and honesty that the rhetoric of discovery is now used. And the progressive de-emphasis on discovery has made it harder to resist the tide of the bogus, the spurious, and the headline-grabbing but insubstantial claims.

For example, last year, a great and coordinated media buzz was created in Europe around the so called ‘discovery’ of a cache of drawings attributed to Caravaggio, located in the Castello Sforzesco. According to the media reports, a ‘group of experts’ had determined that around 90 drawings among a cache in the collection of this Castello were firmly attributable, by virtue of a ‘geometric standard’ to the innovative Italian seventeenth-century painter. e-books were available for sale, Italy’s La Repubblica, a major newspaper of record, endorsed the discovery and the ‘experts’ responsible.

But examination by published and peer-reviewed experts revealed the ‘experts’ responsible for the discovery had never published a word on Caravaggio. The ‘group’ boiled down to two people, and the geometric standard was almost entirely bogus. Art historians then began the serious work of challenging this entirely bogus theory but not before a certain version of truth was ‘out there’ and the damage done. Partly the problem was that the will to discovery was so great – the story of unveiling of hidden and priceless material – that the voices of the academy were not concerted, skilled or persuasive enough to combat it and kick the story into touch, and of course, the academy could be cast as naysayers and sceptics, orthodox and unimaginative.

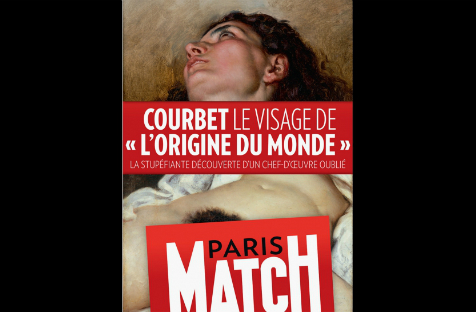

Perhaps the most egregious of recent examples of the bogus discovery in Art History was the recent cover of Paris Match, the Parisian news magazine better known for its celebrity scoops than for its art historical rigour. The Match ran the story that an amateur had found a missing piece of Courbet’s Origine du Monde, the head of the mistress of Courbet,that had been at some point excised from the torso.

The Match article had the voice of an ‘expert’, curator of the ‘Courbet museum’ and science deployed. Of course, it took only a few days for people to realise everything that didn’t add up, including the obvious disjunction of angle and pose and the fact that clearly the ‘original’ painting would have needed to be chopped on all sides for this to have the remotest plausibility.

The problem is that the damage is so hard to undo. In a deep sense this ‘discovery’ was motivated by the most conservative of tendencies, (i.e. recuperating this extraordinary and daring challenge as a run of the mill nude portrait of an artist’s mistress) but worse it reduces to a sub-Da-Vinci-code tale of mystery and restitution. The complex history of the commissioning, creation and ownership of the painting from Khalid Bey to Jacques Lacan (which has such a lot to tell us about making, patronage and of course about the relationships between sexuality and vision) was lost.

Another, perhaps less clear cut example, also replete with art historical lessons for the alert, concerns perhaps the most famous and canonical of all paintings. The ongoing discussions of the so called Isleworth Mona Lisa (left) is another, more raw and complex example of what happens when the debate about a painting almost completely short circuits the academy and takes on a life of its own.

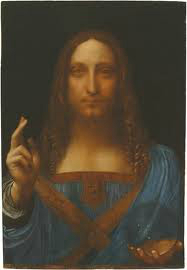

Of course, the serious world of academia and the museum establishment have not entirely abandoned discovery to the lunatic fringe. Some exciting and moving discoveries of recent times, include the re-finding of an astonishing and beautiful painting by Bronzino (above) in the museum at Nice revealed in 2010 and Leonardo’s rediscovered Salvator Mundi (below).

However, all these examples are of only kind of discovery story that seems to make the headlines – which is a variant on the eternal rags to riches folktale – the one which propels Antiques Roadshow and almost all other popular versions of discovery shows – the sudden jump in value of the individual object by virtue of its identification or attribution- great and compelling stories.

But I want to argue, crucially not the stories that will move the field on or contribute to the widening or deepening of our sense of what our discipline could or might be. They almost always concern disputed or ‘lost’ works by famous painters, painters whose oeuvre is already the focus of enormous attention. At their worst, they are utterly corrupt self-interest, but even the most genuine, tend only to add to the existing knowledge or oeuvre of already famous artists, and reinforce these canons (or 10 best lists!) of what is great art.

The sense of discovery I want to revive is a more patient, more thoroughgoing, more collaborative, and indeed transferrable one, the idea that in Art History, (as in science, or archaeology) we do not live in the realm of the settled, but of the mostly unknown and always potentially disruptable).

In Art History we live in a world of ‘orphan objects’, objects often removed in complex circumstances from their original locations and contexts, but always (by definition) at some remove, big or small from their time of making and their first point of reception and objects whose value and interest is not fixed at this Ur- point but needs to be championed, sustained, revived, explained in time and through time.

Slightly closer to what I mean by broadening or at least deepening discoveries is the case of a private dealer who recognized in a Paris antique shop two works by the late seventeenth century woman artist Mary Beale. This discovery informed The Tate Britain’s reassessment of rhe place of women in British art, reshaping how they told the story.

Again in the last year or so, an early career scholar walked into an auction room in Paris and came across a drawing that was of the utmost importance in sorting out one of the enduring mysteries in the still enigmatic career of the great painter Fragonard.

This is new knowledge that came about by a combination of sharp eyes, well-trained minds and enormous subsequent archival work but began with an alertness and an openness to the possibility of discovery, a hunger to answer the ‘what’ question, which then enables new and exciting ‘why’ questions.

This article is an edited extract of the University of Sydney’s 2013 Insights lecture, Art History and Discovery.

(Pictured: Pick the fake Mona Lisa (Answer in the text).)