Installation view David Goldblatt: Photographs 1948-2018, Museum of Contemporary Art (2018-9); Photo Artshub.

South Africa is one of those countries we inherently know – we know its story of Apartheid, its racial struggles, its mineral resources, and its political icons. Yet it’s a country that many of us have not visited.

However, spending time with the photographs of David Goldblatt one almost feels like they have been on that journey across continents. Through Goldblatt’s photography we see the story from the inside, beyond the propaganda and beyond the media grabs and history books.

David Goldblatt: Photographs 1948-2018 is the most comprehensive exhibition of the artist’s work ever assembled, not only in Australia, but internationally. Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s Senior Curator Rachel Kent had the opportunity to work with Goldblatt on this exhibition over a two-year period, sadly cut short with his death last year (25 June 2018).

She said: ‘His work is quintessentially South African, very specific to a time and place, but there is also a universality to its language. These are shared conversations about very important topics.’

Kent said that is was her travels with Goldblatt around South Africa that she, ‘learnt to see the country through his eyes’.

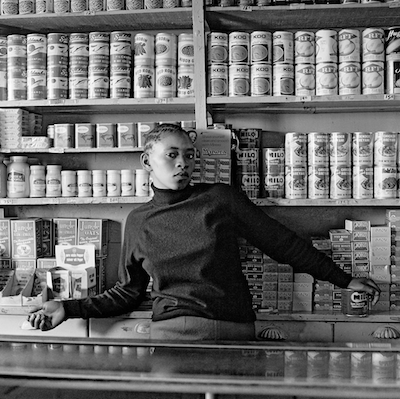

David Goldblatt Shop assistant, Orlando West, 1972, silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper; Image courtesy Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town © The David Goldblatt Legacy Trust

There is a strong sense of that shared storytelling and documentary through the exhibition, which has been loosely curated chronologically moving through Goldblatt’s prolific photographic series.

Punctuating the exhibition are archival materials, Goldblatt’s collection of cameras, and to-camera interviews with Goldblatt, who speaks intimately about the making of his images and the personal stories that sit behind the images in the frame.

These personal accounts add a wonderful sense of pause in this exhibition, which is exhaustive, and at times emotionally challenging. It is an almost overwhelming – very raw and honest – take on humanity, on power over people, land and resources, which is expressed across 360 photographs that span 70 years.

Strangely, in all that turgid past and dismal future, there is a quietness to this exhibition. You want to take time on this one.

While Goldblatt is perhaps best known for his images of Apartheid, he equally documented the injustice of labour in the mines, the displacement of Indian and Malay communities in Fietas (who were forcibly removed to accommodate white people in the 1970s), to the suburban banalities of Boksburg, an all-white aspirational community. The cropping and framing of these images are particularly charged.

Goldblatt says in the exhibition: ‘I was never interested in making propaganda for anybody, and didn’t allow my photos to be used that way.’

As one moves through the early work the black and white images pop against green, blue and taupe walls, the subjects directly engage the eyes. It is confronting, and slightly haunting, but asks the viewer to check their own values.

There is a section early in the exhibition – with the mining works from memory – where a museum case presents a collection of Goldblatt’s negatives printed out as contact sheets with his notations in hand showing which image he selected to print. It is a fascinating insight in terms of framing, tone, and politicisation of the work.

Installation view David Goldblatt: Photographs 1948-2018, Museum of Contemporary Art (2018-9); Photo Artshub

Moving through the exhibition the scale grows and the colour shifts to the photographs. Most of Goldblatt’s oeuvre was shot in black and white, only moving to colour and large format prints in the early 1990s. It was around this time he turned to the post-Apartheid problem of AIDS, which manifests in his series In the Time of AIDS.

Kent said what hit her hardest were Goldblatt’s series of Dutch Reformed Churches – which also sit in this large gallery space – seeming cool modernist architectural structures and yet standing as bastions of power and social injustice. As the saying goes, “the devil’s in the detail” in these images.

Installation view David Goldblatt: Photographs 1948-2018, Museum of Contemporary Art (2018-9); Photo Artshub

The exhibition concludes with two of Goldblatt’s later series presented in a single gallery: the large scale image of desolate landscapes that capture environmental rape and degradation, and the University of Cape Town student protests of 2015, that demanded, and ended with, the removal of a statue on the ground of Cecil Rhodes – a champion of racist colonialism.

Goldblatt was astonished by the reckless destruction in the wake of the #RhodesMustFall movement, as artists thoughtlessly destroyed important artworks by black artists.

Facing these works are Goldblatt’s series Asbestos, which display another level of thoughtlessness. In these Goldblatt juxtaposes the asbestos mines of South Africa and Western Australia where, post-mining activity, companies simply walked away from these site leaving ‘asbestos trailings to blow in the wind,’ as he describes.

On first glance they look like desolate, scarred landscapes, but upon learning their context they become living nightmares in our backyard.

What this does is bring home Goldblatt’s images – to remind audiences that the topics he photographed are global, and indeed local. Paired with the students passion for protest, which also points to the global problem of complacency for dialogue and democracy (its easier to make noise than real solutions), the sum of this exhibition is a powerful message.

Looking across this enormous exhibition, one tends to forget that Goldblatt wasn’t schooled as a photographer, especially given his capacity behind the lens. His father was a Jewish storekeeper and he was forced to continue the business. It was only when he died in 1962 that Goldblatt took on his passion full time.

What he did have was an incredible ability to filter the noise, and connect with the truth of the moment. Many of his subjects engage directly with the viewer. In that, it makes for a very moving exhibition – you become witness to this incredible past, and are called to check your own position on the social in/justice of today.

These problems still exist, and inequity is not only at large in contemporary society, but a growing situation.

‘It’s not just a reminder of the past,’ said Kent. ‘It’s a reflection of what’s happening today.’

Rating: 4 ½ stars ★★★★☆

David Goldblatt: Photographs 1948-2018

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney

Until 3 March

Ticketed