Installation view: Lindsay Kelley, Ballistic Bundts, 2018; ballistic gel and expended bullets, dimensions variable, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Marinco Kojdanovski.

The promotional blurb for this exhibition reads: ‘Art, science and speculation converge in Human non Human, an exhibition posing the question: what makes us human, and how might humans adapt in the future?’

It sounds totally on point with the contemporary zeitgeist in the arts – a place where science, technology, art and ethics converge in a testing ground for new partnerships across organisations and creatives.

It is not surprising then to learn that Human non Human, presented by the Powerhouse Museum (MAAS) is part of an Australian Research Council Linkage Project, Curating Third Space: The Value of Art-Science Collaboration, in partnership with University of New South Wales Art & Design.

Launched during Sydney Science Festival, it almost bristles with a sense of the moment.

The exhibition’s co-curator Katie Dyer told ArtsHub that the project had been two years in the making. She explained: ‘I think people are really responding to this moment in time, where there is both anxiety and desire for the ability and capacity of technology. It is so present in the mainstream and in the discourse – are the robots really coming? You can see it in televisions and in the movies – there is the real sense of, are we going to be displaced?’

She believes we all have a bit of scientist in us. Together with co-curator Dr. Lizzie Muller, UNSW Art & Design, Dyer and her colleague have created a tight show that talks about complex ideas.

Four installation works are informed by scientific fields and aligned to the themes Food, Work, Sex and Belief. The artists are Lindsay Kelley, Liam Young, Maria Fernanda Cardoso and Ken Thaiday with Jason Christopher

The exhibition space, however, is a little awkward – as a viewer you are not entirely sure where this exhibition starts and where it finishes.

Approaching it from one angle, it is Thaiday’s work that visitors first encounter: a collection of Dance Machines and headdresses. Thaiday draws from ancestral Torres Strait Island marine symbolism, which is merged with contemporary materials and robotics created with artist Jason Christopher. As the gallery explains: ‘these unique creations show the adaptability and resilience of cultural forms in the face of technological development, and the deep histories of body augmentation and transformation.’

Ken Thaiday with Jason Christopher, Beizam Triple Hammer Head Shark, 2016; cast aluminum, stainless steel, aluminum extrusion, steel, perspex, rubber, electronic components, computer system, audio; courtesy of the artists. Photo: Jason Christopher.

Dyer said that the works demonstrate the ‘adaptability and resilience of cultural forms in the face of technological development, and the deep histories of body augmentation and transformation.’

The installation adds that engaging, splashy tech-aspect that is a hit with Powerhouse audiences, large numbers of school groups, and families.

The piece, however, that captured my imagination was Lindsay Kelley’s Ballistic Bundts – yes cake tins that are used to make bullet-riddled cakes made from ballistic gel. It is a kind of lab set-up with glass display cases – the kind you usually see in your favourite patisserie, not museum.

Installation view: Lindsay Kelley, Ballistic Bundts, 2018; ballistic gel and expended bullets, dimensions variable, courtesy of the artist. Photo: ArtsHub.

Kelley uses a gel that is commonly used as a human flesh simulator in military weapons testing. Her inedible delicacies address the interwoven relationships between food and military technology, and the growing concern of providing food on a global scale.

Kelley’s archive of bundts draws from the museum’s collection, and was a newly commissioned work for the exhibition.

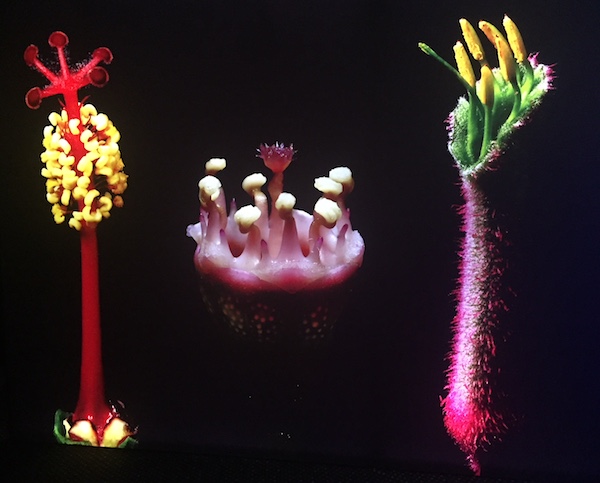

Installation detail: Maria Fernanda Cardoso, The Marriage of Plants, 2018; deep focus photography (top), light boxes, preserved flowers, variable dimensions; courtesy of the artist.

Maria Fernanda Cardoso similarly blurs the worlds of humans and plants asking, who’s manipulating who?

In her project On the Marriages of Plants, she uses deep focus photography to capture intricate floral sex organs, and draws on research that looks at the critical role of plants in human survival.

It is a layered piece, using old museum cases and vitrines, fake flower specimens, and a kind of haunting presentation of black walls and dramatic photographs that seemingly catches the viewer like a Venus flytrap.

Liam Young, stills from Renderlands, 2018; HD video, 10 minutes, courtesy of the artist.

Liam Young’s video installation gets a little lost, physically, in the space – easily passed by. It’s a shame as it is a fascinating piece. He uses discarded digital assets from the animation industry to speak about the increased outsourcing of Western animation to render-studios in India – merging fiction and documentary.

Dyer said that she ‘loved the idea of different knowledge systems’ in this exhibition, and feels that we still exist in an entangled mess – a kind of material mess – and that those actors and agents add to the experience of being human.

You can only agree with her. This exhibition is a great bridge from a place of techno-anxiety to a more human acceptance of technology. It demonstrates that even in a future non-human world, we will not bu entirely post-human.

‘We are not totally ephemeral or digital yet,’ Dyer concluded.

Rating: 3.5

Human non Human

Powerhouse Museum, Ultimo

7 August 2018 – 27 January 2019