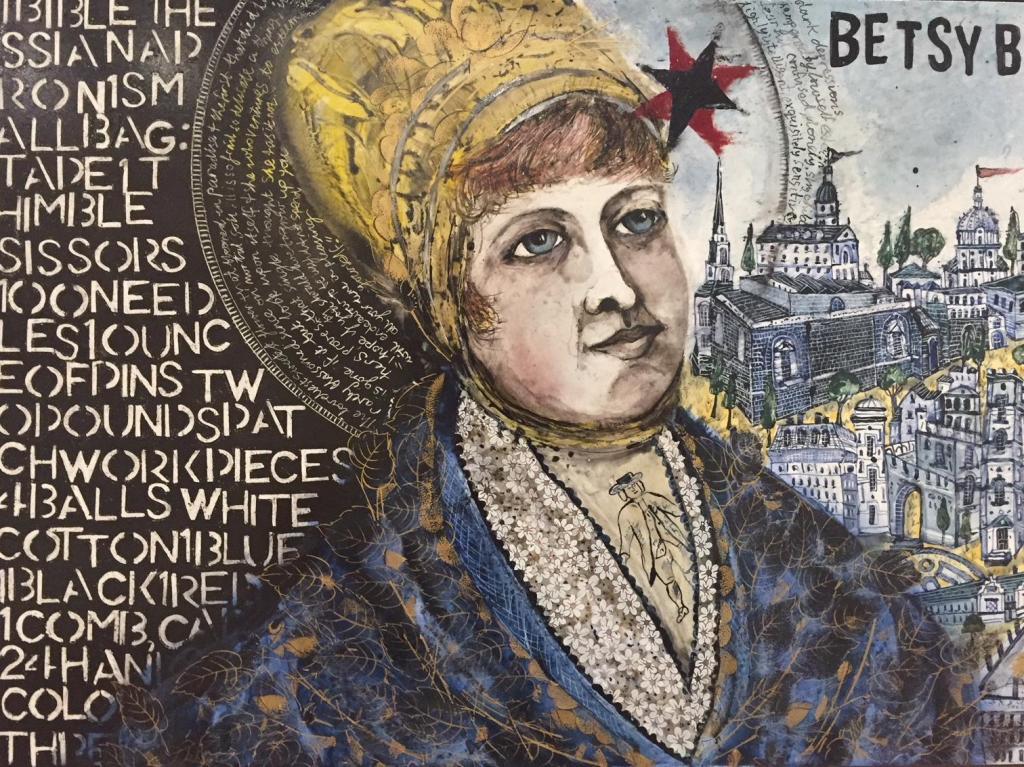

Bern Emmerichs, CrossStitched (2018) detail, painted and fired ceramic tiles; courtesy the artist and Scott Livesey Gallery. Photo: ArtsHub.

Giving ten artists the opportunity to rewrite history is an interesting exercise. What stories do they deem important? And what stories do they feel need rewriting?

That is what curators Sarah Engledow and Christine Clark did for the exhibition So Fine: Contemporary women artists make Australian history, currently on show at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra.

The exhibition was commissioned to coincide with the gallery’s 20th anniversary, and was intended to enrich contemporary narratives around biography – particularly given that collectively, the gallery’s holdings document our national history – and to ensure that women’s voices were part of that narrative.

‘For decades, the principal historians of Australia were men; Australian history was about the activities of men, and Australia’s best-known artists were men,’ explained the curators.

The obvious question, then, is whether a women’s version of history would by so different? If this exhibition, testament to an unleashing of long muffled voices, is anything to go by then the answer is clearly yes. So Fine is sensitive, nuanced, inclusive, tactful, patient, resilient and worthy. It looks both to the past and to how historical omissions impact understanding today.

Clark added: ‘The women – of various ages, cultural backgrounds and demographic groups – present first encounters, convict experience, the suppression and survival of Indigenous people, the betrayal of children, the divided self of the immigrant and the excitement of scientific discovery.’

Overall this exhibition is surprisingly cohesive aesthetically, given the diversity of these ten artists and the reach of the narratives shared. There is an embrace of materiality and sense of hand in the work that ties the exhibition together – without falling into stereotypes of a female domain. These are agile and erudite contemporary art works, and have been curated together beautifully.

Simply, it is a great show, and an absolute gift for the inquiring mind.

Installation view, Carol McGregor and Pamela See in rear; So Fine at National Portrait Gallery, Canberra (2018). Photo: ArtsHub.

What does a women’s take on Australian history look like?

Walking into the space, viewers first encounter the works of Melbourne artist Bern Emmerichs, Wathaurong-Scottish woman Carol McGregor, and Brisbane-based Pamela See.

Immediately you get a sense of the cultural reach of this exhibition, but without it feeling disjointed or forced.

Emmerich’s quirky ceramic pieces are inspired by the convict women who sailed to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) on the Rajah in 1841. They are obsessive in their detail, and yet, have a playful quality that seduces the viewer into this tale. An installation of re-used fine bone chinaware arranged in the shape of Tassie is a treat!

Similarly, McGregor turned to stories less told. She explained of her work: ‘The Great Australian Silence is a term conceived by historian W,E, Stanner for his 1968 Boyer lecture series “After the Dreaming”. Stanner referred to the prevalent, systematic blanketing and omission of Aboriginal perspectives and stories from the accounts of Australian history.’

With this as her cue, McGregor has created contemporary possum skin cloaks decorated with totems as a testament to personal oral histories. They are paired with the installation Not silenced (2013), comprised of 6000 Staedtler pencils, emu feathers, paper and a school desk – a powerful comment on how history is taught in our education system.

Carol McGregor, details of installation not silenced (2013), as presented in So Fine at the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra (2018). Photo: ArtsHub.

Pamela See continues the narrative of invisibility, combining the traditions of European silhouette portraiture and Chinese papercutting to present the lives of 16 Chinese-Australians – innovators and entrepreneurs who contributed to a burgeoning young Australia, but have gone largely unacknowledged.

See explained: ‘I was not aware that during the nineteen century – in some areas of Australia – Chinese settlers outnumbered their European counterparts ten to one.’

In the central gallery, that narrative shifts tone. Nicola Dickson sets her paintings against elaborate colonial-toned “sets” with a backdrop of hand-blocked wallpaper – they feel like museum exhibits of Pacific explorers; an authoritative history constructed by 18th century males.

Her work is beautifully paired with that of Bigambul photomedia artist Leah King-Smith and Melbourne-based Fiona McMonagle.

McMonagle looks at Britain’s child migrant scheme, which operated from the 1920s through to the late 1960s and which forcibly resettled over 130,000 children in Australia. In her body of work The Scheme, McMonagle has portrayed children preparing to embark on this journey in propaganda poster proportions.

Installation view: Fiona McMonagle, The Scheme, in the exhibition So Fine at the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra (2018). Photo: ArtsHub.

Similarly re-thinking the portrait and historic photographs, King-Smith montages photographs of her mother in the series Dreaming Mum again. Extended with handwritten stories, King-Smith attempts to move photography forward from its colonial, canonical role as documenter of history, fusing disparate moments, places and emotions together to offer a more accurate version of the portrait.

Completing the exhibition are works by Pakistan born artist Nusra Latif Qureshi; Scottish-born Canberra-based weaver Valerie Kirk; Gija woman Shirley Purdie, with a grid of 36 painting that speak of country, culture and women’s stories; and Sydney sculptor Linde Ivimey, who honours Australian scientists in the Antarctic.

Of note, Qureshi’s portraits with their web of red threads is a clue for reading this exhibition. Everything is connected – somewhat difficult to unravel – but connected nonetheless in building a picture. It is this premise that sits core to So Fine – to ensure the stories of women are woven into the historical narrative at our nation’s premier gallery of portraiture.

Nusra Latif Qureshi, details of installation Refined Portraits of Desire (2018), as presented in So Fine at the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra (2018). Photo: ArtsHub.

As Qureshi explained of her work, the threads link the subjects in a collective desire for a better, more refined time.

Working from late 19th and early 20th century portraits of women taken at two commercial studios, Qureshi paints their image in the negative, asking, ‘How did they want to be seen? What can we read in the clues?’

She said: ‘I compare their gazes to those in the present day selfie, as they convey an equally powerful desire to be admired.’

She makes the very subtle point that as women today – just as these women then – have the capacity to control and direct how we are pictured, and yet we still grapple with how we are portrayed.

4 ½ stars: ★★★★☆

So Fine – Contemporary women artists make Australian history

National Portrait Gallery, Canberra

Until 1 October

Ticketed exhibition, children free