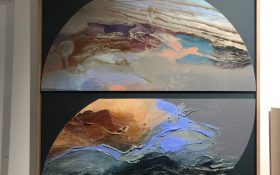

Installation view Tony Tuckson – the abstract sublime (2018) at Art Gallery of NSW; photo Artshub

In many ways Tony Tuckson is both an enigma and totally familiar. He was a stalwart of the Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW) for twenty three years, moving from the positions of cleaner, to curator and eventually Deputy Director (1950-1973). But as his art administration career escalated, this public persona as an artist retracted. It was the reason why Tuckson’s work was rarely shown during his lifetime.

Director Michael Brand observed: ‘Alert to the ethical conflicts between his role as a curator and a life as an exhibiting artist, Tuckson pursued his painting practice in isolation.’

However, for anyone who has an interest in Australian art history or abstraction, they would be familiar with the work of Tony Tuckson. Today he is regularly featured on the walls of art galleries nationally, however, to view a survey across the breadth of his 30-year practice is a rare moment.

Curated by Denise Mimmocchi, Tony Tuckson: the abstract sublime corrals around 70 paintings and works on paper, ranging from the late 1950s to early 1970s. Moving across this exhibition, which is charted chronologically through themed chapters, it has a heroic quality.

The only other comprehensive look at Tuckson’s work was a memorial retrospective held by the Gallery in 1976, followed by a touring survey organised by the Heide Museum of Modern Art in 1989, and another by the National Gallery of Australia in 2000.

Despite painting from 1948, when Tuckson graduated from East Sydney Technical College, to his early death in 1973 at just 52, he only ever showed twice. First in 1970 when he started to withdrawn from his curatorial responsibilities at the gallery. The second just months before his death.

In her catalogue essay, Mimmocchi says that Tuckson’s painting ‘and indeed Tuckson’s oeuvre – like his curatorial work in the museum world – insists that the drive to transform was a defining feature’, adding that his adherence to ‘the energy of gesture and line, the energy of colour and light; the energies of the natural world; the energies of the psyche – determined the shape of Tuckson’s art.’

It is indeed palpable, that energy is easy for audiences to trace across this exhibition.

The journey for the viewer starts with a suite of framed works hung in a salon-style – colourful abstractions that echo Ian Fairweather and Paul Klee. But this first gallery is divided in tone, as we are witness to the early transformations of Tuckson. By the end of the 1950s he had already shed any hint of figuration and moved into his “scribbly paintings”, aka Cy Twombly-influenced marks that float and score the surface. They were his first sustained series of abstract expressionist works.

What is interesting to this introduction to Tuckson’s foundations is a pair of museum cases central to the gallery that tell the story of his discovery of the art of Melville Island and Yirrkala, Arnhem Land with travels there in 1958 and 1959.

He’d seen the earlier exhibition Arnhem Land art at David Jones Art Gallery Sydney in 1949, and acquired his first bark painting in 1952, while parallel the New York School were establishing their practices, with the artist and critic Barnett Newman declaring in 1948 that ‘the Sublime is now’.

Installation view Tony Tuckson – the abstract sublime (2018) at Art Gallery of NSW; photo Artshub

We see that parallel conversations that would dominate Tuckson his whole life, looking at artists like the Americans Twombly, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, for example, with equal weight and influence as the graphic marks of Indigenous Australia.

As an art administrator, Tuckson was visionary in cementing the first commission ever of an Aboriginal artwork for an art museum; as an artist these two things increasingly came together into a language that was distinctively his own – and would leave a great legacy to Australian abstraction.

The exhibition continues to journey viewers through subsequent bodies of work – next his ‘red, black and white paintings’ made between 1961 and 1965, what Mimmocchi ponders Tuckson ‘perhaps considered the impact of New Guinea Highland shield designs’.

These red and black paintings are paired with a small group of Tuckson’s drawings on newspaper, which he was prolific making from his home-studio. I perhaps would have liked to have seen more of these given the foundation drawing had during this period working through idea and gestures, and really the kind of day to day practice he maintained outside his working life.

Installation view Tony Tuckson – the abstract sublime (2018) at Art Gallery of NSW; photo Artshub

What is fabulous as a viewer looking at these newspaper drawings, is the way he plays with the existing columns and format of the papers, and how his marks sit and play with that structure, only for the paper to disappear and the gestures to find their own life on his canvases.

The results we see in the next two galleries, as the works become larger in scale and Tuckson turns to sweeping veils of paint to capture the light. At first they are fleshy and earthy in tone, gradually moving to a bolder palette.

Installation view Tony Tuckson – the abstract sublime (2018) at Art Gallery of NSW; photo Artshub

And so the pendulum swings again; in 1967-68 Tuckson visited the USA on a study tour, where he saw Abstract Expressionist painting, and at that same time, New York’s Museum of Modern Art sent Two Decades of American Painting to Australia (1967). Rather than a constant push-pull, Tuckson increasingly finds his own maturity in resolving these two as one.

Mimmocchi describes the final room in the exhibition as ‘climactic in feel and force’, and a ‘spectacular conclusion to the pathways of abstraction in his art.’ It is clear to any viewer.

This journey, however, is not complete until the viewer walks to an adjacent gallery where the exhibition Melanesian art: redux curated by Natalie Wilson ushers them through the collection of objects and artworks collected by Tuckson for the Gallery from the Sepik region of Papua New Guinea.

Installation view Melanesian art: redux (2018) at Art Gallery of NSW; photo Artshub

The first works of Pacific art entered the Gallery’s collection in 1962. He travelled to the Sepik region of New Guinea in 1965, and just four months later curated the ground breaking exhibition Melanesian art (20 April – 22 May 1966) with over 370 works. It was the most comprehensive exhibitions of Pacific art held in an Australian gallery at the time, and attempted to move these works beyond purely an anthropological lens.

In the years that followed (1968-1977) the Gallery acquired over 500 works from collector Stanley Gordon Moriarty. Together they were part of a vision that Tuckson held to have a dedicated Pacific and Aboriginal Gallery within the new building for the AGNSW he was working on in the years before his death, and the first in Australia.

44 works from that original exhibition and collecting activity have been represented in Melanesian art: redux – a dense, yet elegant hang.

It is probably not the kind of exhibition one would expect to find in the contemporary galleries, but Tuckson taught us a great lesson, one which AGNSW reminds us of again today.

Why now? The Tuckson show is a logical bridge to rethink this collection, but I am also wondering about a global shift in play, as the Royal Academy London currently presents its significant exhibition Oceania (29 September – 10 December 2018), the 9th Asia Pacific Triennial currently at Queensland Art Gallery Gallery of Modern Art presents the work of Gunantuan (Tolai people) among other Islander communities in this contemporary context.

Furthermore, New Guinea was a focus area for APT7 (2012) which also showed Graham Fletcher’s series of paintings Lounge room tribalism, celebrating mid-century modernism and its celebration of “primitive” objects and textiles equally with design. Is this where we are at now, the cusp of a new revival?

Just as Tuckson planned for these conversations to be valued in the planning of the new gallery redevelopment in the 1970s, perhaps this pairing offers a hint of the AGNSW forethought as it starts to plan for an imagine the Gallery’s future with Sydney Modern.

Whatever, the outcome, we are sure that Tuckson will be a sustaining legacy – as both collector and artist.

4 ½ stars ★★★★☆

Tony Tuckson: the abstract sublime

Melanesian art: redux

Curator Talk with Denise Mimmocchi at AGNSW, Wednesday 30 January 2019 5:30pm – 6pm

17 November 2018 – 17 February 2019

Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney