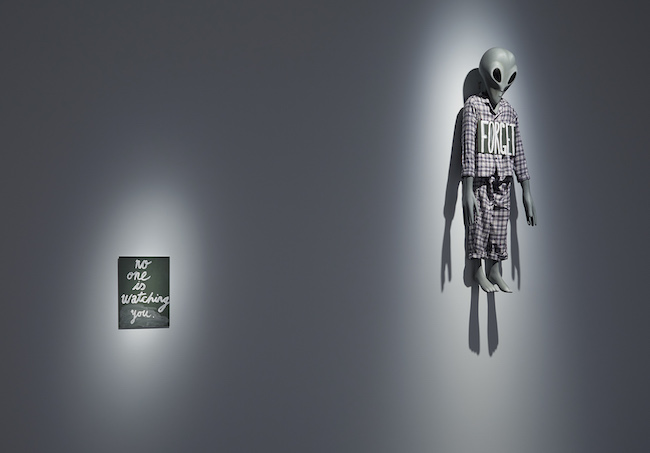

Installation view, ‘No one is watching you: Ronnie van Hout’, Buxton Contemporary, University of Melbourne; photograph Christian Capurro

Distinctive, intelligent, disarming, honest – these are the words that Curator, Melissa Keys uses to describe the work of artist Ronnie van Hout. Turning to a distinctive style referred to as ‘existential absurdism’, van Hout’s sculptural installations, videos and text works evoke familiar and yet strange interior worlds, unleashing deep social anxieties and feelings of self-consciousness. They leave the viewer caught between the impulse to both laugh and cry.

Keys has curated a major solo exhibition of the New Zealand-born, Melbourne-based artist’s work for Buxton Contemporary, Australia’s newest art museum.

Ironically titled No one is watching you, Keys said that the 80 works in the exhibition ‘are broadly grouped to suggest a series of sustained ideas and approaches taken by the artist throughout his practice, which now spans more than 30 years’.

It is the first survey exhibition featuring an artist from the Michael Buxton Collection. Keys told ArtsHub: ‘We plan to program three exhibition seasons annually with the intention that one of these seasons will showcase a major solo project. We see these projects as collaborations between Buxton Contemporary and the artists we work with.’

The gallery has worked with van Hout to commission significant new works for the exhibition.

‘The artist and I worked in close collaboration to create an exhibition environment that sets the scene for his characters and narratives to unfold.’

Keys said she hoped visitors would become absorbed in van Hout’s irrational and humorous ‘micro’ worlds, which are populated by aliens, failed robots, lonely figures and, of course, van Hout himself.

‘Life is a strange, unstable and often isolating experience, and Ronnie’s work provides us with a vehicle for laughing at the difficulties and complexities of contemporary existence,’ the curator said.

Installation view Erstaz (Alien), 2003, ‘No one is watching you: Ronnie van Hout’, Buxton Contemporary, University of Melbourne (2008); photograph Christian Capurro

Art as self-medication

Keys told ArtsHub: ‘Ronnie has frequently commented that he sees himself as more of a filmmaker than an artist and his works often either reference cinematic history, quote film dialogue and performance, or embody the devices, tropes and spirit of sci-fi, horror or arthouse flicks.’

Van Hout’s playful practice also references slapstick, music, cartoons and art history. ‘It exists within the expanded field of theatre and spectacle.’

Keys said that van Hout has been an important artist for as long as she can recall. ‘Perhaps the ideas and artistic occupation of creating, imagining and monitoring “self” makes it highly relevant, engaging and captivating for contemporary audiences,’ she said.

Ronnie van Hout, End Doll, 2007 (detail); UC/APC-1173, University of Canterbury Art Collection, Christchurch, New Zealand. Reproduced with permission

Ideas about the mind, psychoanalysis and illness run throughout van Hout’s practice. ‘He has said he considers art to be more of a symptom of existence than a cure. He has said that “if we [humanity] were well we wouldn’t need art.”

Keys spoke at length about the monochrome panel, Hold that thought, Salazopyrin (2008), presented in the first gallery of the exhibition and which engages notions of the therapeutic properties and potential curative role of art.

‘Ronnie created the work by crushing his arthritis medication Salazopyrin into a fine powder to make a pigment. He then used the pigment to coat the surface. He thought that if “looking at art was supposed to make you better, then looking at medicine as art should be even better.” It’s both an absurd and poignant proposition,’ she explained.

How does one navigate the highlights of this exhibition? Keys said: ‘His is a consistently intriguing and compelling practice and it’s difficult to isolate particular moments within the exhibition as highlights.’

The exhibition opens with the major installation BED/SIT (2008), which references the histories and aspirations of modernism – particularly minimalism. Keys said it ‘provides a strong entry point to the exhibition’.

She added: ‘This room is followed by spaces that suggest encounters with aliens and unseen forces, and which feature classical cinematic alien figures, watchful owls and pajama-clad sculptural figures hovering in strange and bewildering states of being.’

Keys also made note of the new work Bad Fathers, made for the survey exhibition.

‘It presents a cacophony of masculine signifiers and figures from across history, including the Bible, mythology, classical sculpture, history painting, sci-fi cinema, performance and rock music brought together within a critical and farcical comic strip sensibility. Bad Fathers definitely provides a climactic, over the top ending to the show. And, as for everything in between, I encourage you to visit the exhibition and see that for yourself.’

Located within Melbourne’s Southbank arts precinct at the University of Melbourne’s Victorian College of the Arts (VCA), Buxton Contemporary houses the Michael Buxton Collection, recently gifted to the University. This is the new gallery’s second exhibition.

Ronnie van Hout, No one is watching you

Curated by Melissa Keys

12 July – 21 October 2018

Buxton Contemporary

University of Melbourne, Southbank Boulevard, Victoria

Free entry